What we learnt building an enterprise-blockchain startup

It has been almost a year since the idea of HyperVault was first conceived. In that time, we built HyperVault up from a single sentence, gained and lost team members along the way, developed a functional proof-of-concept over the short winter holidays, crashed out of a few competitions (also won a couple of prizes), and finally decided to open source. This post aims to be an honest reflection on the journey – highlighting both the good bits and the times we wanted to give up.

What is HyperVault?

At a high level, the idea behind HyperVault is to use distributed ledger technology (we preferred to avoid the B-word) to provide a secure access layer to sensitive digital resources. If your company has some super-secret documents, what’s the best way of sharing them with other people? From our market research, we found that most people would just chuck it into an email as an attachment. This is terrible from a security standpoint: system administrators can see everything that goes through and you have absolutely no access record or control whatsoever once the email goes into your ‘sent’ mailbox. HyperVault provides a provably tamper-proof system with smart sharing features, such as scheduled or location-based access.

The Beginning: October-November 2018

HyperVault was born at a Hackbridge cluster – a fortnightly meet-up for Cambridge students who want to build side projects. Li Xi had been thinking about the applications of private blockchains in file sharing and met Robert and a group of other undergrads who were interested in joining the team.

By far the hardest part of our HyperVault journey was balancing our desire to build something with the Cambridge term structure. An 8-week term, packed with lectures and supervisions, doesn’t give you much time for entrepreneurial activities. However, we were excited enough about the idea to have weekly team meetings in a comfortable room at Trinity College, where we focused on defining what exactly we wanted the product to be.

At the same time, we were on a constant lookout for startup competitions that we could enter. Fortunately, Li Xi and Robert were also on the Cambridge Blockchain Society – one of whose sponsors (Stakezero Ventures) was launching the Future of Blockchain competition. This proved to be critical to HyperVault’s progress because it gave us a “fixed point” on the timeline – whatever happened, we needed to have a working product and polished pitch by March 2019, when the competition was scheduled to happen.

Winter, literally and figuratively.

December was tough. We had to transition from talking at a high level about what kind of features we wanted to offer, how cool it’d be if we could do XYZ, into actually building a working prototype. To ensure that everyone was on the same page regarding the expected time commitments, in the last couple of weeks of term, we made a detailed project plan that outlined the deliverables, due dates, and expected time commitments (we concluded that it’d be at least 12 hours a week each).

Three team members dropped out at this point. There weren’t any hard feelings – it is understandable for people to have conflicting priorities and it is better that they can say so upfront. This left Li Xi and Robert the considerable task of building a proof of concept, with Andrew taking the lead on the business plan. With the reduced manpower (and a good helping of classic underestimation), the weekly commitment was closer to 30 hours. It was a real hustle having to balance this with academics (and of course, winter festivities), but by the end of the holidays, we had our proof-of-concept. The main lesson to be drawn from this is the importance of having that “hard conversation” with your team. Give people the option to call it quits at the start, but have a “no ifs, no buts” understanding that come what may, your prototype/MVP must be done by a certain date.

The build-up to the competition (January – March)

At this stage, our proof-of-concept was something like a Google Drive or Dropbox, except with a blockchain backend. We were on track, so moved into “Phase 2” – doing real market research and nailing down a business plan. Andrew tapped into his network at the Judge Business School to get feedback from his peers, which was incredibly useful. One of them mentioned that our product offering was quite similar to something they had used in a previous job. This was very worrying, and after some further googling we were deeply troubled to find out that there was a whole class of products – virtual data rooms – that were doing exactly what we had offered. Robert and Li Xi were a little discouraged by this, but Andrew reminded us about a very important fact of entrepreneurship: you never have to be first, you just have to do things better.

Additionally, one of the oft-repeated pieces of advice from successful entrepreneurs is the need to focus on a very specific niche (a ‘vertical’) rather than trying to build a one-size-fits-all product. We saw that the incumbents had dominated the market for financial companies, so we decided to devote our attention to legal companies. With this in mind, we sat down as a team to really think through our business plan – we found the concept of a ”lean business canvas” enthralling – its almost scientific approach to iterating your product via hypothesis and experimentation really appealed to us (indeed, all three of us have a STEM background).

Competition time (March, April)

Coming up on March, our academic commitments were noticeably picking up. But there was no time to waste, as it was competition-season. We agreed as a team that for any competition, there would need to be at least two of us there (three was unrealistic).

The first competition we entered did not go so well – we failed to convince the judges, who traditionally favoured biotech ideas, that blockchain was anything more than a fad. Despite making it to the finals, it was clear that there was very little engagement with our idea. At the time, we blamed the judges for being too closed-minded, but in retrospect, we see that it’s really our responsibility in the pitch to sell the vision we have. Nevertheless, we used the feedback to refine our business plan and tidy up our proof-of-concept.

The main competition in March, however, was much more engaging and challenging (more than 100 teams participated). Due to a last-minute change of competition dates, Li Xi cut short his travel plans and flew back from Geneva for the Finals – luckily, he made it back just in time for the pitch with only a few hours to spare and the pitch went quite smoothly. The judges were intrigued by the idea and asked us some particularly challenging technical questions regarding encryption, which Li Xi dealt with deftly. Coming out of it, we won the £2000 Future of Blockchain Nucypher prize, which was a strong vote of confidence.

The last competition we attended was the R3 Global Pitch Competition. R3 is an enterprise blockchain software firm working with a large ecosystem of more than 300 of the worlds’ largest companies. Even before the submission of our deck, R3 provided excellent guidance by connecting us to their legal teams and having numerous calls with us to refine our business plan, for which we were immensely grateful. We did well in the competition, winning a place in the global finals and subsequently being offered free office space at R3’s office in London to continue building HyperVault.

The end?

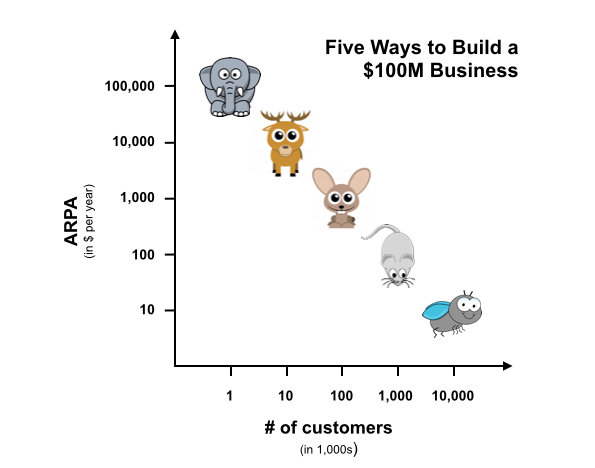

With this opportunity in mind, we were talking to VCs about the idea of scaling up. In particular, we had good chemistry with the folks at Stakezero and Wilbe Ventures, and they gave us a lot of very thoughtful advice, emphasising the importance of not just identifying a vertical, but also targeting the size of the customer and the key stakeholders in a company that could make things happen. We hadn’t put too much thought into this before; I guess we were implicitly making the naïve assumption that if we built a cool product, it would sell itself. Up until that point, in our team meetings, we had just said that we’d target “SMEs” (small and medium-sized enterprises). But after a lot more research and discussion, we came to the troubling realisation that our ideal customer was, in fact, an “elephant” – an organisation that would spend more than $100,000 a year on our product (see this excellent short blog post for more) – they are the only ones who have 1) enough secure documents and 2) a need to share these documents with scalability.

Regardless of our successes in talking with smaller companies, big companies are an entirely different ball game. You need enterprise sales teams and a polished, audited product. In principle, there was nothing stopping us. We could have used R3’s office space to turn our proof of concept into a sleek MVP and earnestly begin the search for venture capital on the back of that. But ultimately, none of us felt particularly excited by this prospect. A startup is hard work – many hours spent fixing bugs, refining pitches, cold calling hundreds of companies, etc. The only thing keeping it together is the deep desire to build something and a fundamental belief that your product can “change the world”. Faced with the prospect of an enterprise sales cycle and a product which is really an improvement over current technology instead of something brand new (don’t get us wrong, we do still think it’s a major improvement), we realised that HyperVault as a commercial startup had run its course, at least until we had more experience.

What comes next

We truly believe that distributed ledgers applied to file-sharing could be a significant improvement over current technologies. To that end, we decided as a team that the best way forward would be to open-source our codebase, such that it becomes an example of a real-world enterprise blockchain app for others to build on.

We published most of our code on GitHub a few months ago and have already had someone reach out to us expressing interest in incorporating HyperVault into their product. We plan to continue cleaning up the codebase within the next couple of months, including comprehensive documentation and a contributors’ guide. Do leave a clap or comment below if you think this is something we should devote more time to!

In any case, rather than inserting some banal Edison quote about failure, we’d like to end this post simply by saying that we are extremely grateful for the friendships we made, the people we met, and the chance to tell ourselves that we built something from nothing.

This post has been cross-posted on medium