How I Read Books

I recently launched a website to open-source some of my book reviews. To accompany this, I’d like to share some thoughts on my philosophy of reading books, and how my current workflow reflects this philosophy.

This post primarily focuses on non-fiction because it is an area in which I think I have “edge” – I am confident in my ability to extract value from non-fiction books. I do enjoy fiction (and discuss it briefly at the end), but I don’t feel qualified to teach someone how to appreciate it.

Contents

- Motivation

- Interlude: spaced repetition

- Spaced repetition and reading

- What to read

- Reading the book

- Processing highlights (a week after finishing the book)

- Writing a review

- Second brain

- Fiction

- Conclusion

Motivation

What do I want from a non-fiction book? I distil this into my reading triplet:

- Retention: remembering what key ideas the book contains.

- Understanding: internalising the ideas well enough to explain them to someone.

- Contextualisation: knowing how the book relates to other books and how its ideas fit into my “second brain”.

My reading workflow has evolved over several years and hundreds of books to optimise for these goals. It has not evolved to maximise the number of books read, nor my retention of an individual book. I say “evolved” rather than built because it’s been an organic and iterative process, that is still being improved!

I truly believe that reading books, when done properly, can be a competitive advantage.

Interlude: spaced repetition

Before continuing, I will take a slight detour to discuss spaced repetition, a key component underlying my reading philosophy. If you are already familiar with the concept, feel free to skip this section.

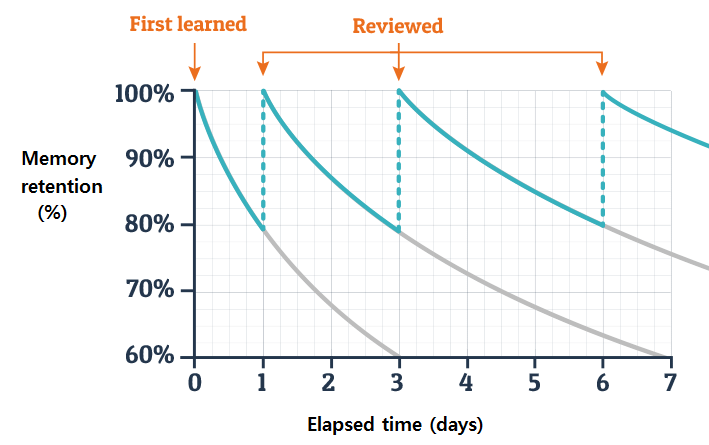

After learning something new, we tend to forget it over time. In the late 19th century, psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus tried to quantify this experimentally (rare for psychologists at the time!). One of the results of his research was the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve, which plots how retention changes as a function of time (it is roughly $e^{-kt}$).

More importantly, Ebbinghaus figured out that active recall of the content (testing yourself) not only refreshes the forgetting curve but makes it decay more slowly subsequently.

This leads to the idea of “spaced repetition” – refreshing your knowledge at particular intervals to maximise retention. Spaced repetition is the core philosophy of flashcard systems like Anki and RemNote, which I heavily relied on during my time at university and truly were a meaningful contributor to whatever academic success I may have had.

Spaced repetition and reading

How does the idea of spaced repetition apply to reading books? In a personal productivity workflow, repetition is a bad thing. It takes up time, adds no value, and should be automated away. But if retention is a variable for which you are optimising, repetition is a good thing. As such, my reading workflow is deliberately inefficient (more on this later).

This is why I refuse to use Blinkist or read summaries in place of reading books (despite being the kind of person who consumes youtube/podcasts at 1.5-2x speeds). In a typical non-fiction book, the author spends several chapters building up the thesis and providing motivation for it, with loads of examples along the way. The repetition aids retention and the examples help you contextualise the information. This philosophy also suggests that you shouldn’t necessarily read books in one sitting – so I typically choose to read several books in parallel rather than reading sequentially.

Note that while I would not use book summaries to replace books – they can be excellent accompaniments. In the spirit of spaced repetition, listening to Blinkist or reading a summary a couple of weeks after you’ve read the main book is a great way of recalling the core ideas of the book.

What to read

I use Goodreads to track all of my reading: books I want to read, am reading, and have read.

I’m liberal when it comes to adding books to my “Want to Read” shelf: I add a book whenever someone gives me a recommendation, a book is referenced by people I respect, or I come across it randomly and it piques my interest. I’ve currently got about 100 books on this list.

When I’m ready to start a new book, I look at the reading list and consider some of the following factors to decide what to read:

- Has the book been strongly recommended by credible people?

- Is the book being referenced by other books I’ve enjoyed? This was why I reluctantly read Taleb’s books.

- I keep a rough mental list of topics I’m interested in (e.g. finance, decision making, science fiction). Any classics in these areas are always fair game.

- If I’ve read a couple of books on the same topic in a row, I’ll try to rotate to something else.

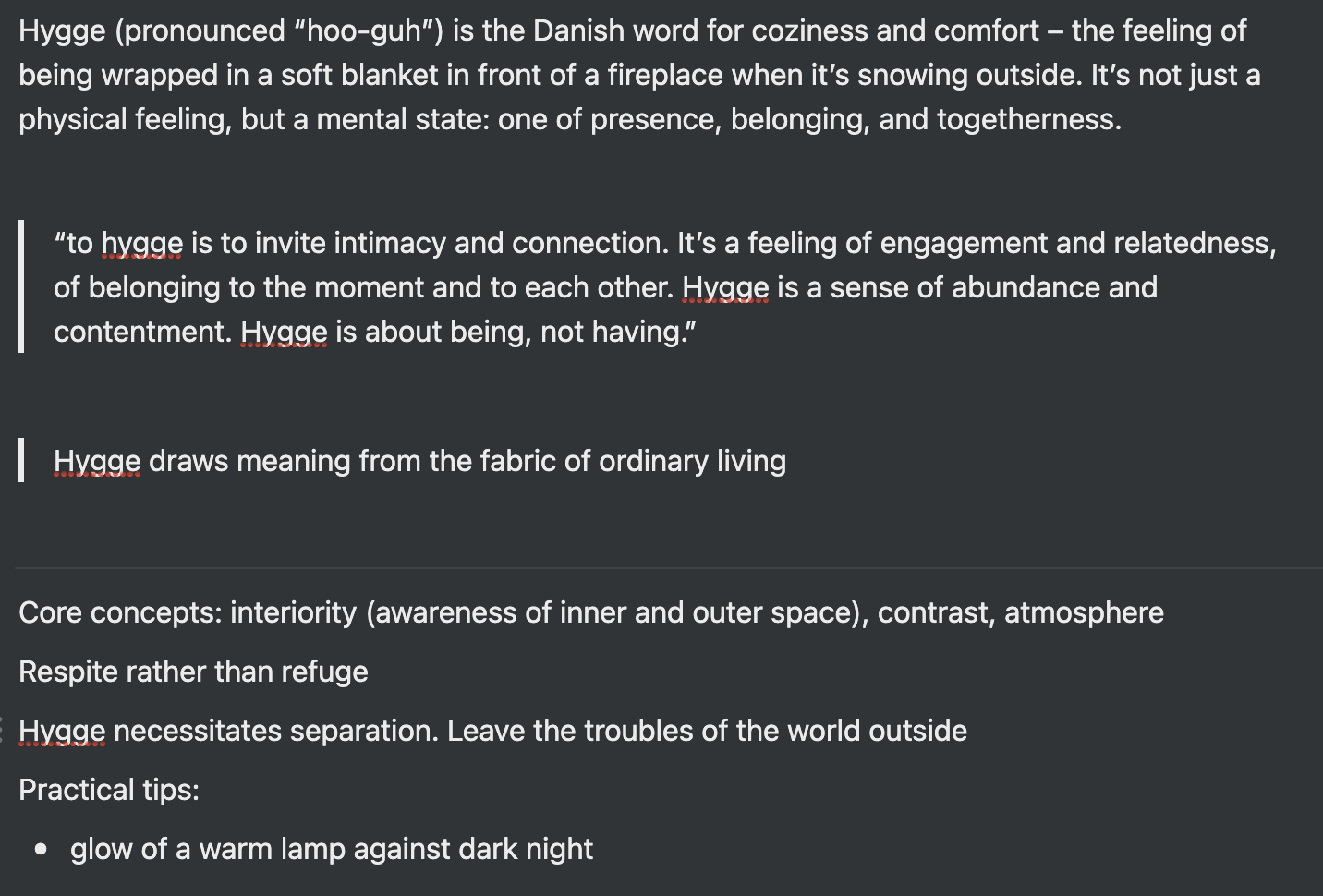

- It’s important to sprinkle in some “rogue” books, completely unrelated to my interests. For example, I recently picked up a book on Danish interior design called The Book of Hygge (my review here).

Ultimately, I’m not as deliberate as I could be with book selection. I think it’s fine to be somewhat organic because it allows your minds to explore “threads” and build connections. Perhaps more importantly, it ensures that reading remains an enjoyable activity. If you have a predefined list of books that you are making yourself read, it becomes a chore – the most dangerous thing one could do in building a reading workflow is to become sick of reading.

Once I’ve decided what to read, I create a blank Notion page for the book (literally just the title).

Reading the book

As much as I love physical books, I read most of my books on Kindle. Even if I had a physical book, I would probably prefer to read it on Kindle (though I will sometimes get the physical copy to adorn my shelf!). The reason for this is the highlighting feature – I can’t understate how much of a game-changer this has been for me.

My guiding philosophy when making highlights is the “funnel”. I highlight very liberally when I’m reading the book:

- Interesting new concepts

- Good explanations for concepts that I was already familiar with

- Anything that feels like a good summary of a key idea

- Phrases I like (e.g. particularly well-constructed sentences)

- Things that make me laugh

- Things I don’t understand

But highlighting something once doesn’t obligate me to care about it in future. In the subsequent stages of my reading workflow, I delete lots of highlights, winnowing them down to only the key ideas.

While reading the book, I also make brief notes in the Notion page if something strikes me as a key idea (though I should be able to reconstruct this from my highlights). I also start thinking about the shape of my book review, though at this stage, the notes tend to be quite scattered.

Processing highlights (a week after finishing the book)

After finishing the book, I let it rest for a while, focussing on one of the other books I’ve been concurrently reading, or just cracking on with other things in life.

About a week later, I start processing the highlights. Firstly, I get the highlights from my Kindle onto my computer, using a little python script I wrote.

I then manually copy these highlights into Notion. Note: there are services like clippings.io or Readwise that can do all this for you, but I enjoy my hacky process and again, in the spirit of spaced repetition, the inefficiency of manually copying highlights isn’t a bad thing.

At this point, in my Notion page for the book, I’ll have some miscellaneous bullet points as well as a tonne of highlights.

The next order of business is to go through the highlights, culling the redundancies. For example, I may have highlighted the author’s first reference to a concept, only to realise that they offer a better summary at the end of the chapter. I only keep the latter.

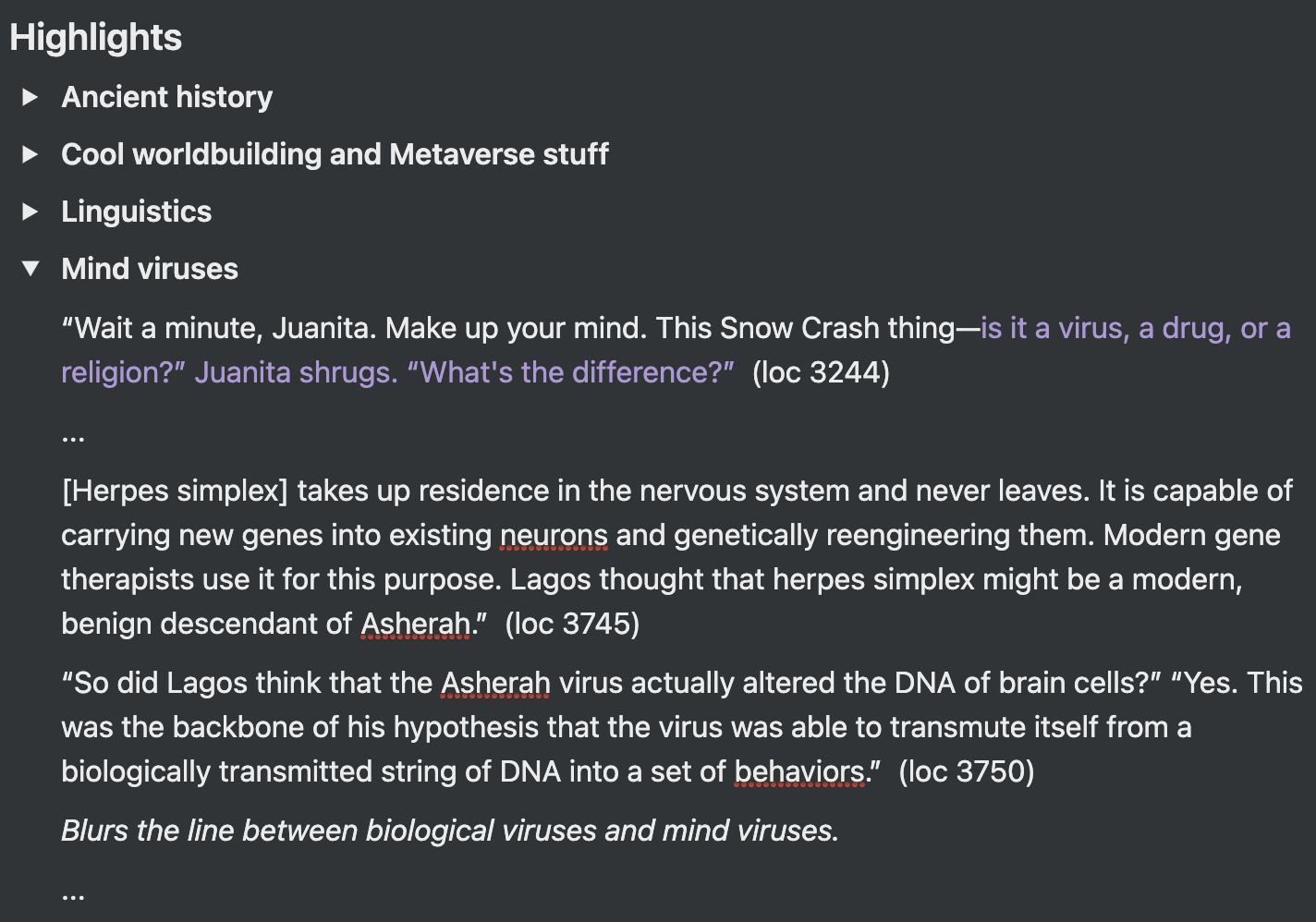

After doing this, I try to group the highlights into different themes. This is a difficult task because it requires you to think on a more abstract level about the key points in the book and how they link together. I am often unable to do it one go; I try for a bit, get frustrated and give up, then return later. I strongly believe that this process, though uncomfortable, significantly improves my understanding of the book. Moreover, it makes it much easier for me to find a specific idea months later.

I also put in the effort to annotate some of the highlights, making a note of why it was impactful to me, what concept it reminds me of, what part of my life it applies to, etc. I use purple to emphasise certain parts of the highlight and write my annotations in italics below.

Writing a review

Writing a review is one of the hardest parts of this process. It entails wrestling with the content and mulling over the categorised highlights to not only understand the concepts the author is presenting but to critically review their originality and how they fit in more broadly with other books.

I don’t have much advice about writing reviews. It’s something that comes with practice and having written 100+ reviews I still struggle. But for each review I try to include:

- The core idea of the book and maybe a couple of my favourite quotes

- How this book is similar/different to others in the genre

- Any interesting links I observed between this book and others (see the section on Second brain below)

- How much I enjoyed the book

At the end of this process, I post the book to Goodreads, and now to my review site as well.

These little things gamify the process, providing a little dopamine hit. Remember – dopamine is the chemical for wanting more, not the chemical for satisfaction (that’s serotonin), so there’s value in associating dopamine with something productive.

Second brain

At this point, I have a book review and categorised highlights (see my book reviews site for examples). To maximise the value I get from the book as per my reading triplet, I then try to integrate the book with my second brain.

A second brain is a network of concepts and ideas that are relevant to your life and interests. I run my second brain in Obsidian. To fully describe my system would require a separate blog post, but it is loosely based on the Zettelkasten method, best described in Sonke Ahrens’ book How to Take Smart Notes (my review here).

Concretely, my process for integrating the book with my second brain is as follows:

- Summarise the book

- Extract atomic concepts

- Growth

Summarise the book

The goal is to distil the author’s core thesis (maybe with a couple of examples to aid memory) in your own words. The points should not be original, but it’s important to use your own words, otherwise it is easy to copy-paste ideas without internalising them.

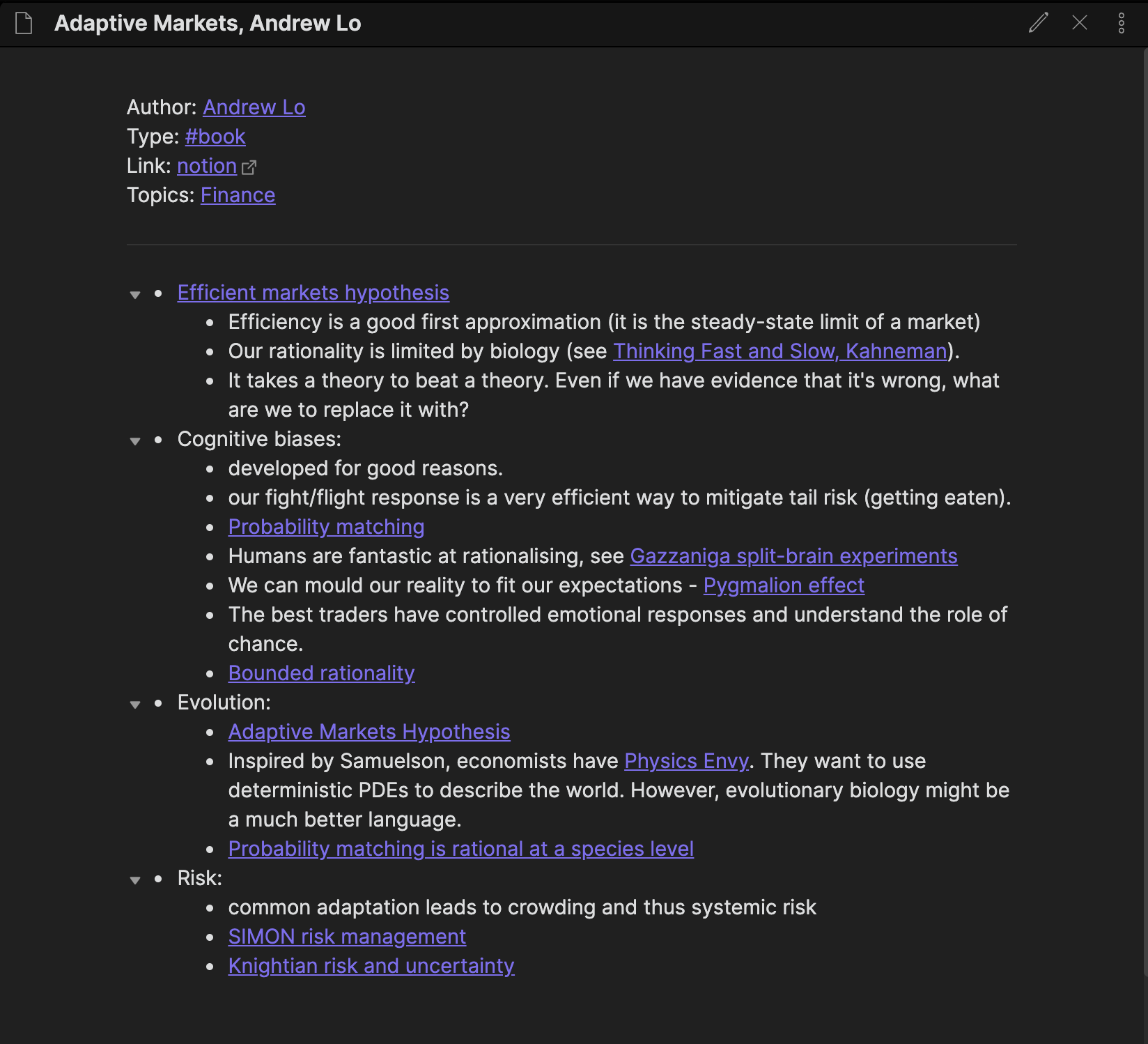

Below is an example of my summary for Adaptive Markets (my review here). I write this summary in Obsidian and sometimes duplicate it on my Notion site for the benefit of other readers.

Extract atomic concepts

My mental model is that a non-fiction book is made of concepts, examples, and commentary. The concepts can either be original to the author, or well-established. Examples are provided by the author to illustrate the concepts. In the commentary, the author discusses how those particular concepts relate to other ideas, or provides a critical perspective on those concepts.

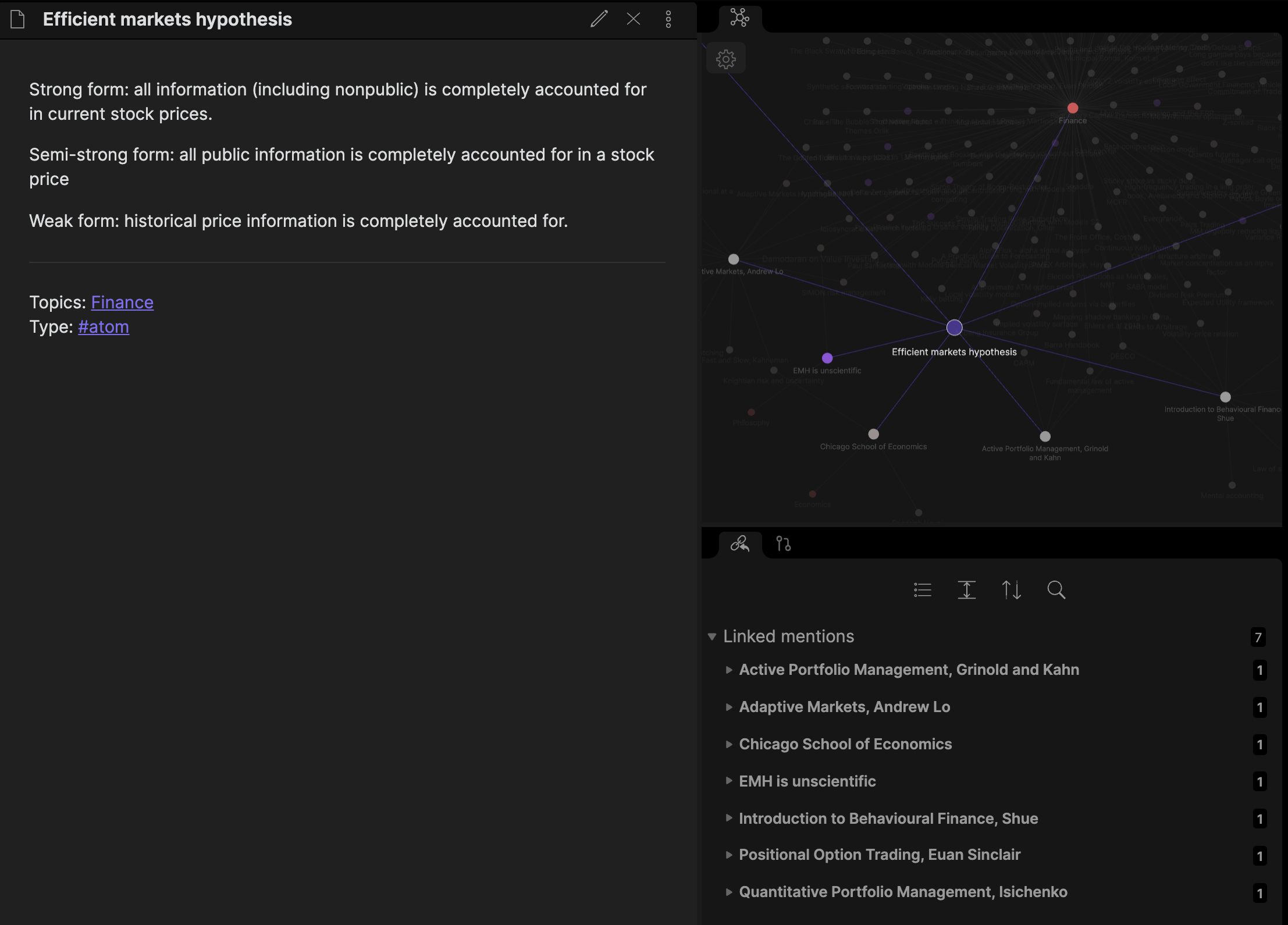

My note-taking approach reflects this model. For example, I try to extract the concepts and examples into individual notes. This avoids unnecessary duplication because they often show up in other books. In the Adaptive Markets screenshot above, the purple text denotes a link to an individual note I’ve made. The efficient markets hypothesis is a concept discussed in several books, so I created an atomic note for it; the bottom-right of the screen shows all the books that point to this concept. Likewise, the Gazzaniga split-brain experiment is frequently used as an example in books on decision-making to illustrate our powers of rationalisation, so it deserves its own note.

This approach also allows me to better understand how the concept fits in with the idea landscape, for example, by looking at Obsidian’s graph view (in the top-right of the screenshot).

Growth

Now that the book is in the second brain, the process doesn’t finish. It instead becomes a “seed” in the garden, whose nourishment is derived from linking it to other concepts.

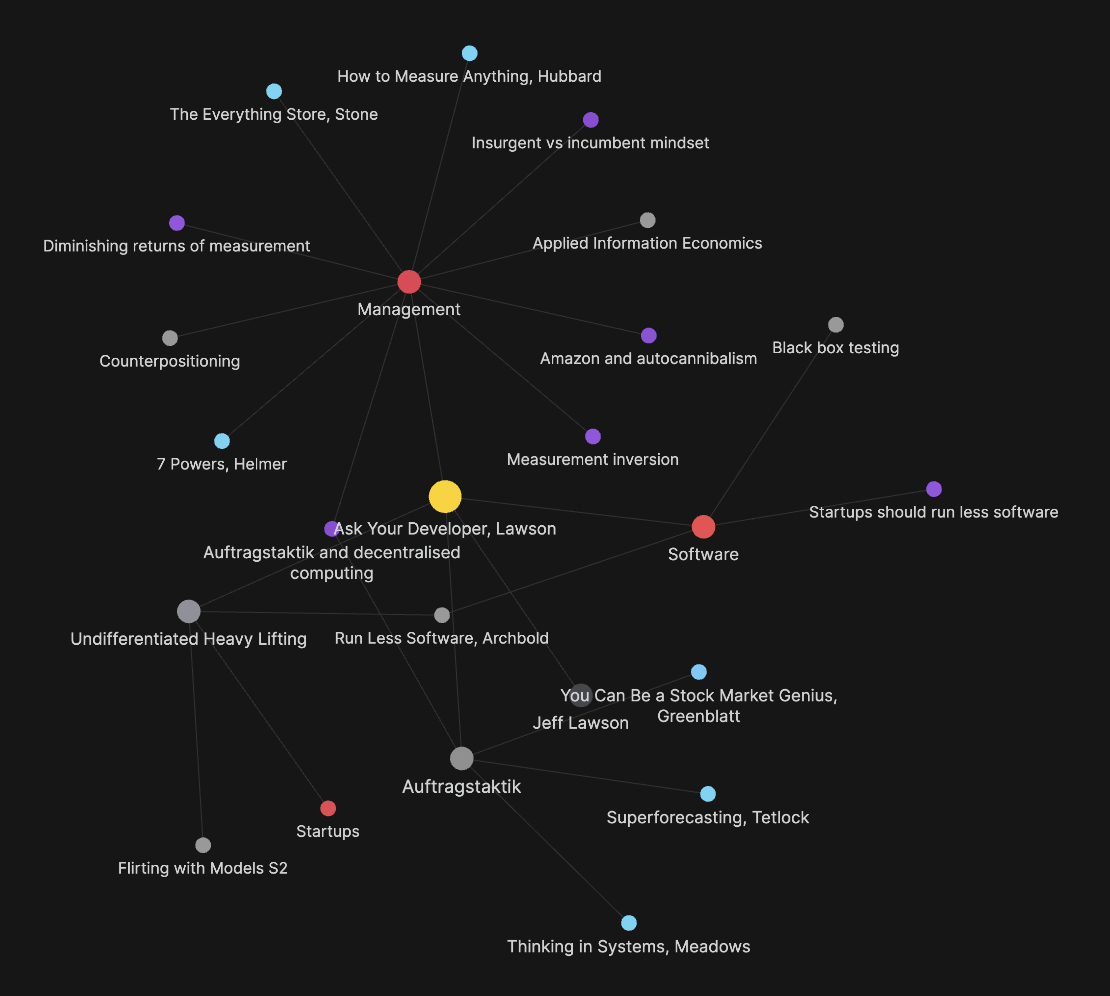

Using the graph tool, I look through related notes – book reviews, summaries of different web articles, ideas I’ve had – to try and find links. For example, after reading Ask Your Developer, a book about managing software firms written by Twilio CEO Jeff Lawson (my review here), I noticed that there were some interesting links to the design of decentralised systems, and therefore a link to German military strategy (auftragstaktik). I add these ideas to the summary page, or if they are meaningful enough, create a separate note for them.

This is the key to building $O(N^2)$ knowledge growth – each incremental piece of content you consume has N other ideas/atoms/sources to connect to.

A key part of growth is discussion! Nothing sharpens your understanding of a book, highlights your misunderstandings, or inspires new ideas like a discussion with someone else. They don’t need to have read the book – the process of trying to convey the key message of the book to someone else really helps your mind distil it, as per the Feynman method. Oftentimes after discussing a book with my friends I’ll come back and modify my summary to reflect newfound understanding.

Fiction

There are several reasons to read fiction.

Firstly, for “culture”. A cynical take is that the only purpose of reading the classics is to tell people you’ve read them. This probably used to be a source of motivation for me when I was younger, but I’ve matured a bit: it’s important to read classic/popular books so that you can understand references, and so that you can enrich conversations by pointing out a parallel to a well-known tale.

Secondly, fiction books often do a good job of illustrating philosophical concepts. Rather than reading a political philosophy textbook to learn the definition of an authoritarian state, you could instead read a dystopian classic. 1984, Brave New World, and Fahrenheit 451 give three completely different perspectives on an authoritarian state; having read all three allows you to make intelligent commentary on what characteristics the real world shares with each of them, and perhaps even gain insight into where we may be headed. I have learnt more about Japanese history from reading fiction (e.g. the work of Yukio Mishima), more about Russian history from reading Dostoevsky, than I would have learnt from non-fiction history books. My perspectives on AI, technology, and the long term future of humanity have been influenced by science fiction.

The last reason, of course, is for the entertainment value. This is purely subjective, but I think reading fiction books provides a different kind of entertainment to watching TV. It requires more effort but can provide deeper appreciation. In any case, it’s not a binary decision: one should read fiction books and watch TV!

Conclusion

My processes are in “perpetual beta” (a concept from Superforecasting by Philip Tetlock) – I’m constantly trying to improve my system for reading books. For example, I’m terrible at giving up books; I feel a kind of petty competition where I refuse to let the author “defeat me”, so once I start a book I feel obliged to finish it. This is clearly suboptimal – there are poorly written books out there and I could unlock a lot of value by giving up and starting a better one. To improve on this, as part of my 2022 reading goals, I have resolved to give up a certain number of books.

The last thing I’ll say is that (to paraphrase Orwell) you should ignore all of this advice sooner than do something barbarous – not reading! Even reading books without making highlights or taking notes is valuable; I didn’t really make highlights or take notes for the first couple of hundred books I read, and while I certainly would have gotten far more out of them had I applied my current workflow, I don’t regret reading those books.