Assessing Human Error Against a Benchmark of Perfection

Anderson, A., & Kleinberg, J. (2016). Assessing Human Error Against a Benchmark of Perfection. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (pp. 705–714). San Francisco, California, USA: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939803

Can we analyse a large dataset of human decisions to discover the instances in which people are most likely to make errors? Instead of using ML to make optimal decisions, we can use it to predict when humans are more prone to error.

Chess is an ideal system to analyse:

- it presents a human player with concrete decisions of different value

- the ground truth, the correctness of a given decision, is feasibly computable.

- chess is non-trivial, even for skilled players.

In order to use chess as a model system, there are three obvious possible approaches (each with fatal flaws):

- Construct problems with a well-defined ground truth (e.g. tactics puzzles). However, it is difficult to amass a sufficient dataset.

- Use chess databases and chess engines to evaluate where people’s decisions have differed from those of the engines. However, it is still difficult to find a mapping between the engine’s move choice and a determination of human error.

- Calculating the minimax value of every position: any move that decreases the minimax value more than a certain amount can be called a blunder. However, this is computationally intractable.

A solution is to exploit the fact that chess has been solved for all positions with at most k pieces on the board (currently $k=7$, from Moscow State University), in the form of tablebases. These are construted by working backwards from terminal positions.

We can start with the large database of recorded games, then restrict them to the positions with less than or equal to $k$ pieces, and compare the move played with the best move according to the tablebase. This gives the added advantage of allowing blunder analysis on fixed positions – seeing how different people behave on the same position.

The features investigated are as follows:

- the skill of the decision-maker (measured by Elo rating)

- the time available to make the decision (measured by remaining time on the player’s clock)

- inherent difficult (measured by the proportion of legal moves which are blunders)

Position difficulty

- In a position $P$ there are $n(P)$ legal moves, of which $b(P)$ are blunders. We impose that $1 \leq b(P) \leq n(P) -1$ (i.e there is at least one blunder and one non-blunder).

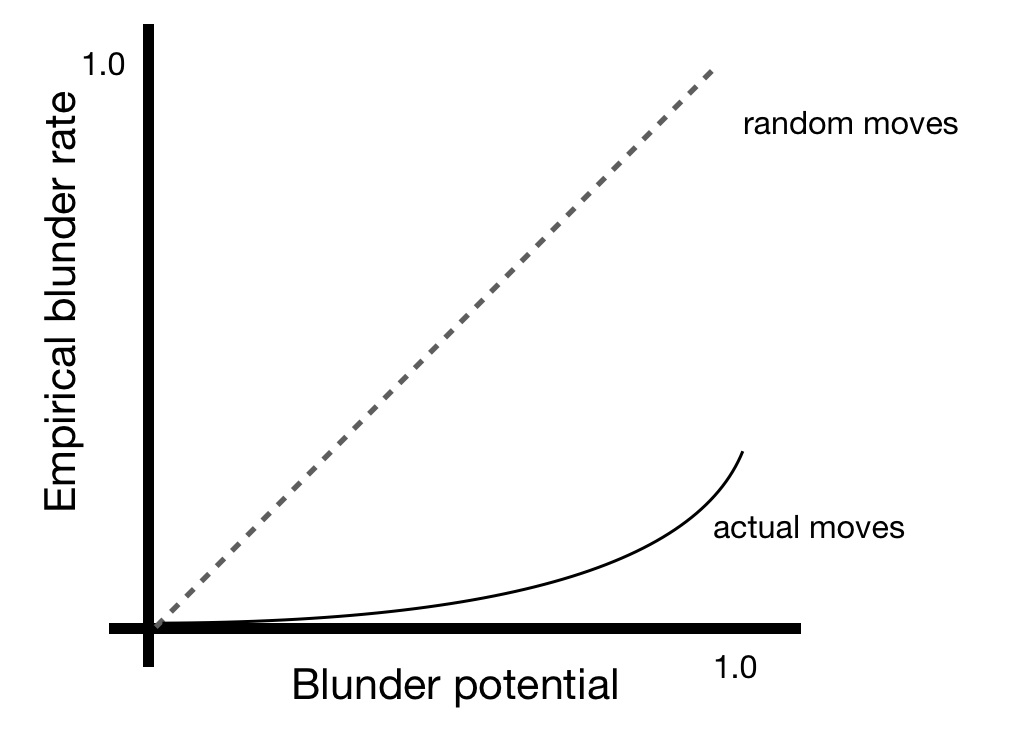

- Empirically, it was found that the blunder rate increases monotonically in $b(P)$. Thus we can define the blunder potential of a position as $\beta(P) = b(P)/n(P)$ – this is not to be confused with the empirical blunder rate.

- A simple model that fits the results suggests that players are $c$ times more likely not to blunder (where $c > 1$). Then, the empirical blunder rate $\gamma_c(P)$ is defined as

- Fitting this model to the data gives a result of $c \approx 15$ for amateurs and $c \approx 100$ for GMs.

Player skill

- The empirical blunder rate is a smoothly declining function of the Elo. This skill gradient looks the same for different $\beta(P)$, but with vertical offsets.

-

$\beta(P)$ seems to very important: an increase in $\beta(P)$ of 0.2 contributes as much to the empirical blunder rate as 600 Elo.

Players rated 2700 are making errors at a greater rate in positions of blunder potential 0.9 than players rated 1200 are making in positions of blunder potential 0.3

- When analysing blunders on fixed positions, it was found that not every position is skill-monotone. That is, in some positions, the empirical blunder rate actually increases as Elo increases.

Time

- The dataset includes a large number of 3-minute games. Define $g(t)$ as the empirical blunder rate with $t$ seconds left. $g(t)$ increases sharply as $t \to 0$, but flattens out for $t > 10$.

- Blunder potential still plays a very important role: an increment of 0.2 to $\beta(P)$ corresponds to an extra 50 seconds.

- For higher skill players, extra time confers a relatively greater advantage.

- More time spent correlates positively with the empirical blunder rate.

Prediction

- Instead of just considering the current position P, we can construct a game tree of depth d, with P at the root.

- If there are n moves, b of which are blunders, we denote the non-blunders as $m_1, m_2, \ldots, m_{n-b}$ and the blunders as $m_{n-b+1},\ldots, m_n$, leading to positions $P_1, P_2, \ldots, P_n$. Let $T_0$ be the indices of non-blunders, and $T_1$ for blunders.

- If $\beta(P_i)$ is high, it will be hard for the opponent to capitalise on your blunder, so you may be less likely to notice that it is a blunder.

- We can thus aggregate the blunder potentials of all the subsequent moves, and use this as a feature:

- For training, a balanced dataset of 600,000 instances was fit by a decision tree with features as discussed.

Results

- Skill and time remaining give 55% and 53% accuracy respectively, while difficulty gives 73%.

- Most of the predictive power comes from depth-1 features.

- Humans have a slightly lower accuracy at predicting blunder positions.

- For positions with only one blunder, blunders became less likely with higher b(T_1) – suggesting that people are less likely to play moves that increase complexity.

- Once position difficulty is controlled for, skill and time give 63% accuracy.

I thought this was a very detailed and honestly fascinating investigation into errors of human decision-making. Of course, it may be difficult to generalise the results beyond chess, but it really is an impressive start.

This doesn’t really feel like your typical comp-sci paper, it’s more of a Kahneman/Tversky -esque piece on decision theory. However, because it is classified as a comp-sci paper on arXiv, I would have liked to see a bit more about the exact implementation, be it code or otherwise.