Stormy Seas for Proof of Work

In this post we will be examining one of the main problems with Proof of Work (PoW) – not the energy inefficiency (as it is debatable how much of a problem this really is), but something more fundamental with the consensus process. In the past couple of months we have seen a number of cryptocurrencies fall victim to 51% attacks. Verge, Bitcoin Gold, ZenCash, and Electroneum are just a few coins that have been targeted, resulting in a total equivalent theft of $5 million (not to mention the subsequent loss in market value of the coins).

51% attacks are a basic problem in distributed ledger technology, covered in any crypto 101 course. Essentially, each individual node in a decentralised network is responsible for validating transactions and optionally submitting a block of these transactions to the blockchain – doing so requires the node to solve hash puzzles (this is why it is called Proof of Work). The beauty of this system is that each node has a say in what happens, proportional to the amount of hash power they contribute – thus the system is a democracy of sorts. However, a natural corollary of this is that any node or group of nodes that achieves a majority of the hash power can ‘outvote’ the rest of the network, allowing them to conduct a 51% attack.

Standard theory dictates that if there are enough independent nodes on a distributed ledger, we can reap the benefits of democracy while knowing that it would be immensely costly for a malicious party to achieve 51% of the hash power. This may be true for cryptocurrencies with many active nodes (like Bitcoin and Ethereum), but with the proliferation of multitudinous altcoins, we may not be able to say the same for more obscure tokens. It is thus the case that 51% attacks have gone from being a textbook problem to something very real, actively destroying both reputation and value in the crypto space.

In this post, we will explore how an attacker might go about conducting a 51% attack, examine the features that make a coin most vulnerable, and comment on prevention and mitigation. An obvious disclaimer: nothing in this post should be construed as a recommendation or a practical guide on conducting a 51% attack.

Malicious actors

It is no secret that cryptocurrency has attracted a large number of malicious parties, ranging from exchange-hackers to phishing scammers. Part of the reason for this is the underlying anonymity/psuedonymity of the system. If someone were to steal one million USD, they would likely require a network of offshore bank accounts to get away with it. However, if you were to steal 200BTC, all you’d have to do is convert it to a privacy coin like monero on any one of the exchanges that doesn’t require KYC, and law enforcement would have a very hard time catching up with you.

In this post we are dealing with a narrow subset of malicious actors: those who play by the rules. There are multiple ways a 51% attacker can ‘legally’ (in terms of the blockchain protocol) use their majority hash power to behave maliciously, one example being the denial of service to users in a network. But by far the most direct way of benefiting at the cost of others is to double spend, which is the when the same coin is sent to multiple parties in a network.

How a 51% attacker might double spend

Once an attacker has identified a suitable target (more on this later), this is a rough sketch of how they might profit. Again, this is purely educational and hypothetical – by no means is it a practical guide.

I will refer to the target coin as TCOIN. Many of these steps also require an anonymous “exit coin” – I will use Monero (XMR) as an example.

- Acquire some TCOIN anonymously, e.g. via an offline swap of fiat for XMR then XMR for TCOIN.

- Set up an account with exchange A and exchange B. Clearly these exchanges should have minimal KYC.

- Send 1000 TCOIN from your TCOIN address to that of exchange A, then immediately cash it out to XMR.

- Acquire 51% of the TCOIN network’s hash power, then make a new TCOIN transfer to exchange B. This transaction should be put into a block that orphans the previous block, so although exchange A thinks they have received your TCOIN and you have cashed it out to XMR, in reality it is exchange B that has received the TCOIN.

- On exchange B, convert TCOIN to XMR and send it to your monero wallet.

In general terms, this describes how the double spend lets you manufacture 1000 TCOIN from thin air (at the expense of the first exchange). An optional additional step is to first short TCOIN, because we have seen that 51% attacks severely reduce public trust in the coin’s development team and tend to lead to a sudden price drop.

Thus far this has all been theoretical – we have presented a textbook situation of how a double spend might work in theory. In the next section, we will understand the worrying practical reality of the situation.

Vulnerability of different coins

One would think that there should be a perfect correlation between the market cap of a coin and its overall hash rate – that is, the demand for a coin should be correlated with the ‘strength’ of the network validation. However, empirically this is not the case. Because of the rise of ill-informed speculation, we see that some coins with a high market cap (a few hundred million USD) have a surprisingly low hash rate. This is the clear yet disturbing message of crypto51.app, a simple site which displays the cost of becoming a 51% attacker (over 1 hour) for different PoW cryptocurrencies.

I submit that there are four main features an attacker would look for in an ideal target coin, apart from the obvious factor of having a smaller hash rate (and thus a lower attack cost).

- High market cap (as a proxy for interest/liquidity in the coin)

- Low transaction time (i.e very few block confirmations)

- Support on KYC-free exchanges

- A common hashing algorithm, or at least one that is supported on a mining marketplace like NiceHash. The advantage of this for an attacker is that they can just rent hash power anonymously rather than having to acquire hardware.

Using python’s requests and beautifulsoup, I scraped the data from crypto51 in order to do my own analysis (available on a Jupyter notebook) of which coins were most vulnerable:

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

r = requests.get("https://www.crypto51.app/")

soup = BeautifulSoup(r.text, "lxml")

data = []

headers = []

table = soup.find('table')

column_names = table.find('thead').find_all('th')

headers = [i.text.strip() for i in column_names]

rows = table.find('tbody').find_all('tr')

for row in rows:

data.append([i.text.strip() for i in row.find_all('td') if i])

df = pd.DataFrame(data, columns=headers)

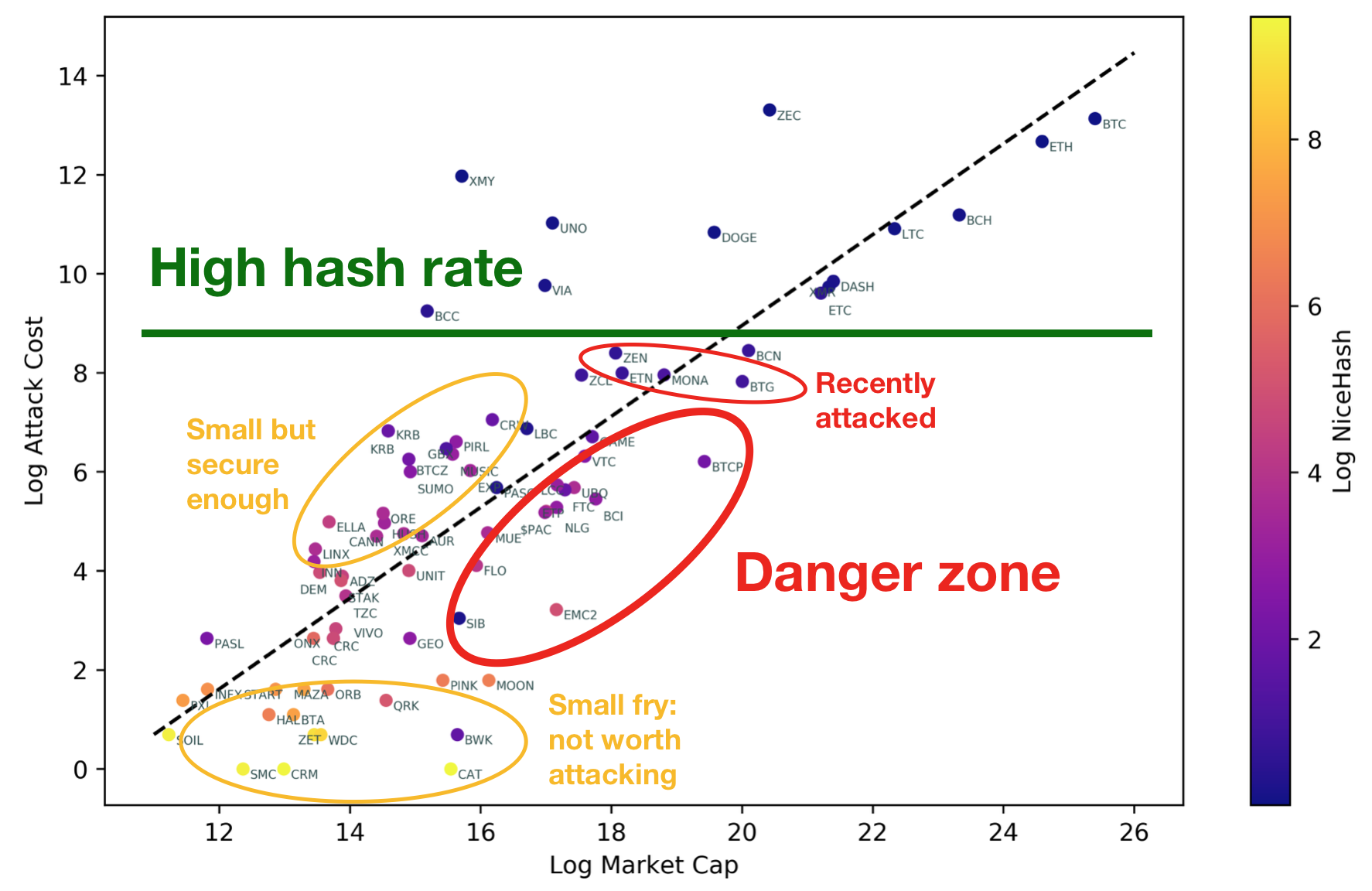

I then processed the data and generated a plot of the attack cost versus the market cap, coloured by NiceHash-ability (all log-transformed). This is very easy to do using pandas plotting:

df.plot.scatter("Log Market Cap", "Log Attack Cost",

c="Log NiceHash", colormap="plasma")

In a graph like this, a target coin should be as close to the lower-right quadrant as possible (high market cap but low attack cost). The lighter the datapoint, the easier it is to attack via NiceHash, which may or may not be important to an attacker.

A linear trendline fits the data with $R^2 = 0.65$, and because a straight line on log-log axes corresponds to a power law relationship, we can calculate the coefficients as follows:

\[\text{1h attack cost} = 8.3 \times 10^{-5} \cdot (\text{mcap})^{0.92}\]Actually, it is not the general relationship that matters but rather the specific outliers – altcoins below the trendline are those with especially low attack costs relative to their market cap.

The top portion is self explanatory. In the bottom-left quadrant are coins that are easy to attack, but also have such small market caps that they are likely not worth attacking (e.g. very poor exchange support). I thus determine the danger zone to be coins with slightly higher market caps (in the order of USD 10 million to 100 million). However, I happened to notice that some of the recently attacked altcoins (listed in the introduction) formed a narrow band slightly above my danger zone. Perhaps this is a liquidity sweet-spot that makes it easier for attackers to exit onto another exchange, or perhaps it’s a coincidence.

In any case, if I were holding something like BTCP (Bitcoin Private), I’d be a little bit worried. It has a market cap of more than \$200 million, and reasonably liquid trading pairs, but costs less than \$500 an hour to attack. If the attacker were unwilling to set up hardware, they might prefer to target something like EMC2 (Einsteinium), which has a higher NiceHash-ability.

EDIT: 3 months after writing this post, BTCP was 51%-attacked!! I hope this post had nothing to do with it.

Now, in a perfectly efficient market, one would imagine that the possible financial benefit from conducting a 51% attack would not outweigh the financial costs. However, recent attacks show that this is clearly not the case (especially because one can now short the target coin prior to the attack). So there is a clear problem in the crypto markets.

What can we do about it?

An obvious solution is to ditch PoW and go with Proof of Stake (PoS). Much easier said than done. Arguably the most mature PoS development effort is that of Ethereum, in the form of Casper. Yet despite the undeniable talent of the dev team, solving the nothing-at-stake problem and ironing out the wrinkles in the implementation is not proving to be a straightforward task. Delegated PoS may be a stepping stone, but the concessions with regard to decentralisation may be a bit off-putting. So assuming that PoW is still the de-facto consensus mechanism, what can the ecosystem do to reduce 51% attacks? Here are some ideas.

Speculators/investors should consider the hash rate of any PoW coins they are looking to invest in, and be aware that a low hash rate makes that blockchain vulnerable for a 51% attack – certainly not good for their investment.

New PoW altcoins should not use the same hashing algorithm as big coins, even if it’s easier to implement – a large miner can just point their hash power at the new blockchain and immediately become a majority. Dev teams for these projects should implement programmatic checks for 51% attacks: a quick response can be critical. Fiat reserves should be maintained, which can quickly be used to add hashing power to the network if a potential 51% attack is detected.

Exchanges should be wary of what tokens they list, and should increase the required block confirmations for transactions, making it more costly for attackers to rewrite the recent history of a blockchain. Yes, this would make it slightly more inconvenient for users, but 51% attacks can directly lead to material losses.

Conclusion

Proof of Work is a genius solution to the distributed consensus problem, and I often have to remind myself just how amazing the original bitcoin protocol is. But I believe that in PoW, 51% attacks should be possible – they are a direct consequence of democracy. For large decentralised networks like that of bitcoin or Ethereum this is not a problem, but owing to the speculative interest in cryptocurrencies, the demand for some altcoins has separated entirely from the security of their network, resulting in a kind of arbitrage which allows malicious actors to profit by conducting a double spending 51% attack.

This post’s analysis of coin vulnerability has not been perfect: the main flaw is our use of market cap as a proxy for the profitability of a 51% attack. In reality, the profitability is a function of block confirmation times and exchange liquidity. Market cap is arguably correlated with the two, but it is not as direct.

I don’t claim to have all the solutions to the problem of 51% attacks, but it is evident that no single party can solve the issue alone. Until the different players (miners, users, exchanges, investors) in the ecosystem contribute their part, coins with low hash rates will continue to be low hanging fruit for the aspiring 51% attacker; I’d wager that we’ll see a few more big attacks before the year ends.