Molecular Notes: Principles

In this post I present Molecular Notes, a note-taking system I created to help me learn from diverse sources (books, textbooks, articles, courses), distil insights, and synthesise new ideas. Molecular Notes is how I approach my Second Brain – the body of concepts and ideas that are relevant to my understanding of the world, both personally and professionally.

In general, I try to seek out mental models rather than specific facts; when I talk to people, I want to understand what models they are using. In a way, this post is my attempt to convey the most useful thing I can: my mental model on thinking, accumulating information, and building mental models – a meta mental model so to speak. As much as I enjoy writing my little explorations into miscellaneous bits of finance and mathematics, I am under no illusion as to their value. They are designed to pique curiosity (primarily my own), explore a neat quantitative technique, or outline an interesting connection. This post has much more grandiose ambitions: to outline my philosophy and practice of learning.

Part 1 introduces the concept of Second Brains and the principles of Molecular Notes. I also compare Molecular Notes with Zettelkasten and Evergreen Notes, two other Second Brain systems. Part 2 covers the implementation: I discuss the software options and provide an in-depth walkthrough of my actual setup in Obsidian, including the practical workflows I use, along with a forkable GitHub repo so you can mimic my setup.

This will be a detailed post; I spend a fair bit of time introducing the subject, as well as laying the groundwork. Use the table of contents to navigate!

Thanks to Niamh Q and Shiv G for reading the drafts.

Contents

- What is a Second Brain

- Objectives

- Molecular Notes

- Why Molecular Notes matters to me

- Who is Molecular Notes for?

- Lay of the land – other note-taking systems

- Failure modes

- Conclusion

What is a Second Brain

My definition:

A Second Brain is a system for consuming and interacting with information (specifically, concepts and ideas) that I care about.

The way I define it, a Second Brain is a subset of “personal knowledge management” (PKM) – my definition does not include stuff like todos, goals, and plans. I bucket those under task management and project management instead (see my post on using Notion for these aspects of PKM). Note: this isn’t universal. Some people choose to include task management within their Second Brain, but I think it’s useful to think of them separately because the techniques and software tools used for Second Brains are quite different to the other verticals within PKM.

Let me break my definition down further:

- “System”: I should have a process, rather than making ad hoc decisions about how to incorporate new information into my thinking.

- “Consuming and interacting with”: my brain is not just a hard drive: it computes across a knowledge graph. A proper Second Brain must provide both functions.

- “Information (specifically concepts and ideas)”: as mentioned above, my Second Brain does not deal with project/task management. It purely deals with concepts, insights, and ideas.

- “That I care about”: the goal is not to have faithful representations of every learning resource I’ve ever encountered. Instead, I want a map of concepts that are relevant to my thinking (personal or professional).

I have been working on my Second Brain for several years, switching between software tools, ripping up my workflows, and evolving my approaches. I am writing this post now because I feel that I have reached a point of equilibrium for the philosophy of my system, although the mechanics are in “perpetual beta” – I’m always tweaking for improvements.

Additionally, I am confident that I can use the system to create value, both for personal development and professional learning. I maintained the system during my internships, using it to effectively learn about complex subjects and derive actionable insights.

Objectives

I, like most of my audience, am a knowledge worker. As Wikipedia puts it, the job of a knowledge worker is to “think for a living” – to consume information, process it intelligently (which may require drawing on existing information or learning new techniques), and then communicate the output to stakeholders.

The underlying goal of a Second Brain is to improve my ability to be a knowledge worker. This manifests itself in several specific objectives:

- Rapidly learning complex topics from mixed media forms

- Retaining insights and understanding

- $O(N^2)$ growth

- Synthesising new ideas

- Encouraging positive learning habits

I address each in turn.

1. Rapidly learning complex topics from mixed media forms

I summarise it thus:

Having a process for consuming sources of information,

In a way that allows me to see how the pieces fit together,

While pointing to more detailed resources should they be needed.

The notes in my Second Brain should not contain all the details – they should only deal in the key ideas. In the internet age, what matters is knowing how concepts connect and knowing what tool to use for the job. If I ever need the details, I can simply refer to the original resource.

2. Retaining insights and understanding

On many occasions (particularly for university), I have put in the effort to truly understand a particular concept – grokking it at an intuitive level. This normally involves reading lots of different articles and scribbling ideas out on a piece of paper until the intuition clicks in my mind.

Then, a few weeks/months later, I realise that I have forgotten the understanding that I worked so hard to gain. This is an incredibly frustrating situation: it’s not trivial to rebuild this understanding since it required me to consult many different sources. A key motivation for the development of Molecular Notes was to prevent this from ever happening!

Specifically, a good Second Brain should allow me to rapidly achieve the same level of understanding about something that I once had in the past. This may be more difficult in situations where that piece of understanding is conditional on many other bits of knowledge, but even then, I should be able to rapidly traverse the local landscape of related concepts so that I may reconstruct intuition.

3. $O(N^2)$ growth

I don’t want my knowledge and capability to grow merely linearly in the number of things I consume. I want my knowledge to grow $O(N^2)$ – quadratically. Doubling the number of things I read should quadruple what I know.

How does one achieve this? With linked thought. Rather than treating each piece of knowledge in isolation, I want to try and link it with my existing body of knowledge. Each new piece of knowledge can potentially connect with all the other things I know.

This is quadratic because the total number of possible handshakes in a room of $N$ people is of order $N^2$ – specifically, $\frac 1 2 N (N-1)$. I want each new piece of knowledge to “shake the hands” of every other piece of knowledge.

Note: it is neither possible nor desirable to have true $O(N^2)$ growth – some pieces of knowledge are simply not related. Rather, this goal exists to emphasise the importance of linked thinking and the super-linear growth that it provides.

4. Synthesising New Ideas

Figuring out how a machine works is important. Better still is to be able to propose modifications and improvements to a system, to invent and innovate.

My Second Brain should not only enable me to get to grips with a complex topic but to have novel perspectives on the topic and to identify new directions to expand into. In the language of educational psychology, creation is at the top of Bloom’s taxonomy.

To be sure, synthesis is not entirely within the purview of the Second Brain system itself – it depends on the creativity of the user’s actual brain, so I don’t treat this as a sine qua non for a Second Brain system.

5. Encouraging positive learning habits

Simply put, the system should spark joy. This largely comes down to the choice of tool: it should be a tool that is customisable and that I enjoy using.

However, there are valuable insights deriving from the literature on addictive technologies. Consider Nir Eyal’s Hook model, described in his book Hooked. Eyal posits that Habit-forming technology requires:

- Trigger: either external (e.g. notification) or internal (e.g. routinely checking the news when you wake up)

- Action: behaviour done in anticipation of reward

- Variable reward

- Investment: user invests time into the product

To the extent I can build a system that follows the Hook model, it will be enjoyable and habit forming.

Summary – Objectives

That’s a lot of different things. But really what I want to strike at is this:

A Second Brain system should allow me to learn from textbooks, online courses, and articles in a way that helps me understand the concepts, and enables me to apply those concepts in my personal and professional life.

Molecular Notes

Over the past several years, I have experimented with different note-taking approaches, ripping my systems to shreds and starting again on numerous occasions. I finally settled on a system that I have come to call Molecular Notes.

I want to emphasise that Molecular Notes is an emergent system – it evolved from many little refinements over the past couple of years, rather than being designed top-down to meet the objectives I laid out earlier. On the one hand, this leads to a more stable and robust system (as is generally true for emergent systems). On the other hand, in writing this post I have found that the emergent nature of the system often makes it surprisingly hard to explain. I will do my best, but if you find some aspects of it unintelligible, the fault is my own. Please send me an email with the offending paragraph and I’ll try to reword it!

The three primitives in Molecular Notes are:

- Sources: any source of information: a book, textbook, online course, podcast, youtube video, academic paper, presentation, etc.

- Atoms: existing concepts or techniques. As a rule of thumb, these will often have Wikipedia articles.

- Molecules (similar to “zettels” in the Zettelkasten system): crystallised insights, pieces of intuition, links between Atoms, my ideas.

These are organised with Topics.

The overall workflow of Molecular Notes is:

Mine Atoms out of Sources, make Molecules out of Atoms, organise everything with Topics.

Sources

A Source is any medium of information that I want to learn from. The main types of Sources that I deal with are non-fiction books, textbooks, podcasts, online courses and YouTube videos.

As I have written previously, my mental model is that Sources (especially books) are typically composed of:

- Concepts: either original to the author or well-established concepts that the author is referencing as part of their thesis

- Additional details, context, and examples to illustrate the concept.

- Thesis: the author gives their commentary/explanation regarding how concepts link to other concepts.

My note-taking approach reflects this model. I want to capture (as briefly as possible) the core thesis of a Source, with reference to some key concepts, along with perhaps one or two of the best examples since these are often good mnemonic tools.

For example, in NNT’s The Black Swan:

- Concept: Black Swans – events that are rare, extremely impactful, and intrinsically unpredictable.

- Examples: NNT provides several examples from finance and history.

- Thesis:

- Most of history is determined by Black Swans

- We should be cautious in learning from the past

- We should collect positive Black Swans

This model is not universal: some Sources, particularly technical ones like textbooks, focus on presenting concepts and techniques, without having a thesis. Other Sources, like opinion pieces, focus primarily on a thesis rather than explaining concepts. Additionally, we need to be a bit loose with our definition of “concept”; for example, Sources about history discuss events rather than concepts, but I mentally lump this under “concepts” nonetheless.

In any case, what I’m getting at is that Sources contain some pieces of knowledge that are “unique” to the Source, and some pieces of knowledge that exist separately to the Source (even if they are frequently referred to by the Source, or indeed invented by the author). Molecular Notes supports this distinction.

I will try to make this more concrete: when taking notes from several Sources, I find that many concepts are duplicated across Sources. For example, the Black-Scholes model is discussed in every textbook about options; the narrative fallacy is explained in many books on decision-making; Kuhn’s paradigm shifts crop up all the time. If I was to re-explain these concepts in every Source note that references the concepts, I would end up with a lot of duplication. Duplication hampers discoverability: the next time I want to re-acquaint myself with “paradigm shifts” by searching for it in my note-taking system, I would be overwhelmed as the definition shows up in 10 sources.

This leads to one of the key tenets of Molecular Notes: we should extract concepts into individual notes – Atoms – and link to them from the Source (modern note-taking software like Obsidian makes this trivial).

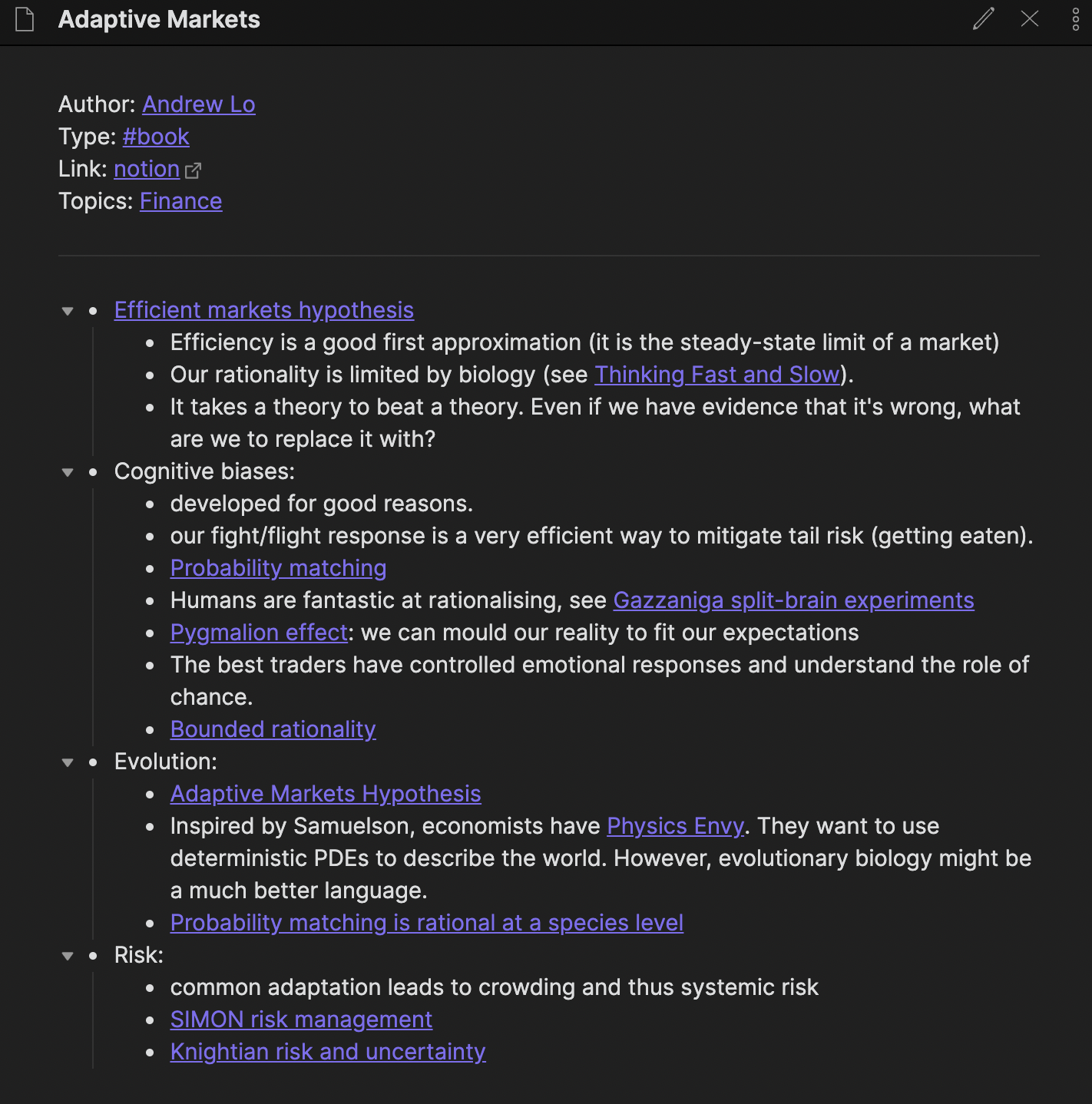

I will explain the philosophy of Atoms in detail in the next section, but I think an example of a Source note will be illustrative. Below is my note for Adaptive Markets by Andrew Lo:

The purple text denotes a link to an Atom I’ve made. For example, the Efficient markets hypothesis is a concept discussed in several Sources, so I created an Atom for it. In the bottom-right of the screenshot, you can see all the other books that point to the Efficient markets hypothesis.

Some judgment is needed to decide what should be extracted as an Atom and what shouldn’t be. As a simple rule of thumb, I extract an Atom if I think it is likely that other Sources will discuss it, or if I think I will link ideas to that Atom specifically. The process of deciding whether to extract a concept is useful in itself because it makes me constantly reason about my notes on a meta level – debating whether something is likely to be useful for my thinking and looking at a Source on a higher level of abstraction.

It is also important to allow for flux. Often my initial notes won’t contain many extracted Atoms until I later realise that a particular concept discussed by the author (for example, black swans), comes up in several other Sources. At that point, to prevent duplication, I extract the concept into an Atom and make all of the Sources link to that Atom. So even when I’m taking notes from textbook A, I’ve got panes containing my notes from textbooks B and C, trying to identify which aspects I can extract into Atoms. For example, I was recently working through an online course on econometrics (left-most pane) which referenced moving-average models. This sounded familiar and I realised I had covered it before in a textbook (the right-most pane). So I combined the explanations from the textbook and the online course into an Atom (middle pane), then made both Sources link to that Atom.

There are certain Sources (especially blog posts and Twitter threads) that only present one concept. In this case, it would be wasteful to create a Source note since it would only link to one concept. So I “cut out the middleman”, making an Atom and directly linking to the Source.

However, if this Twitter thread merely referenced Berkson’s paradox as a part of a broader thesis, I’d be tempted to make it a Source note that would link to the Berkson’s paradox Atom.

In Part 2 of this post, I provide a detailed workflow for how I create organised Source notes for different Source types. But for now, here are some guiding principles:

- The notes should mention all the key concepts discussed by a Source, but should not explain all of these concepts (the explanation should go in the Atom for the relevant concept).

- Aim to reduce the author’s thesis to its simplest form – I shouldn’t feel bad about reducing a book to 1-3 bullet points!

- In essence, the note should tell me what is inside the Source, rather than repeating all the contents. My notes store pointers.

- Regarding structure, I aim for simplicity and flexibility. Consistency is useful but overrated. I like to use nested bullets because they visually emphasise that there are different levels of abstraction. By scanning the top-level bullets, I should be able to quickly get a feel for the thrust of a particular Source. If I need more information, I can start descending into the bullets. If I need more information still, I should just open the original Source!

Summary – Sources

I consume Sources by making notes on them. While making notes, I extract concepts into individual notes called Atoms. These Atoms can be linked to by several Sources.

Atoms

An Atom represents an existing concept, technique, formula, framework, historical event, or historical figure. It is a piece of knowledge that doesn’t “belong” to me – it already exists, and the Atom is merely an explanation of it in my own words.

As a rule of thumb, Atoms are pieces of knowledge that could have their own Wikipedia page (indeed, many of my Atoms do have corresponding Wikipedia entries).

The functions of an Atom are threefold. It must:

- Explain the concept to me, such that I can rapidly resume a level of understanding I once had (Objective #2 – Retaining insights and understanding)

- Show how that piece of knowledge fits in with other Atoms (Objective #1 – Rapidly learning complex topics; Objective #3 – $O(N^2)$ growth).

- Point to resources should I need more detail. Attached to each Atom should be a link to some Source (or even just a wiki page / URL) with the “best” explanation I can find for the concept.

Conveying understanding

I always write Atoms in my own words. This is a critically important part of understanding something. I aim to keep the Atoms very brief, such that I can rapidly get up to speed. In particular, I am not aiming to capture all the details: only the parts of it that are interesting or relevant to my thinking.

For example, the Wikipedia page for the Battle of Alesia (during Julius Caesar’s campaign in Gaul) contains about 4000 words and covers the historical context, details of the Siege, casualty numbers etc. Yet my particular interest lies in Julius Caesar’s tactics regarding the construction of concentric walls, so my note is a mere 90 words (in fairness, the context has been offloaded to another Atom for the Gallic Wars).

Showing how a piece of knowledge fits in with other atoms

I liberally link my Atoms to other Atoms. Additionally, most Atoms refer to a Source and are categorised with Topics, both of which allow me to better understand the context of a particular Atom.

Atoms as pointers

For each Atom, I provide a Reference. This is usually the Source note that discussed the Atom, but more generally, I want a link to the “best” resource for learning more. In the example above, if I wanted to know more about BLUEs, I would click into the Reference (in this case, my Source note for Ben Lambert’s online course in Econometrics), and look at the context in which BLUE was referenced. If that’s not enough, my Source note links to the original resource.

Summary – Atoms

In essence, my library of Atoms forms something like a personal Wikipedia, with several crucial differences:

- My library only contains Atoms that are relevant to my thinking (in the sense that they originated from a Source I felt was worth reading).

- Wikipedia pages aim to be comprehensive, Atoms do not. Atoms should only cover the aspects of a concept that are interesting or relevant to me.

- Because an Atom is written in my own words, it should be easier for me to regain lost understanding.

- Once an Atom is created, it can link to other Atoms and be linked to by other Atoms. This creates a network of ideas that can graphically demonstrate how concepts link to one another.

Molecules

Thus far, Molecular Notes has been nothing more than a system for principled note-taking that seeks to reduce duplication. This is good, but we still haven’t achieved all of the objectives.

- 1. Rapidly learning complex topics from mixed media forms

- 2. Retaining insights and understanding

- 3. $O(N^2)$ growth

- 4. Synthesising new ideas

- 5. Encouraging positive learning habits

The solution: Molecules (a.k.a “permanent notes” in the Zettelkasten system).

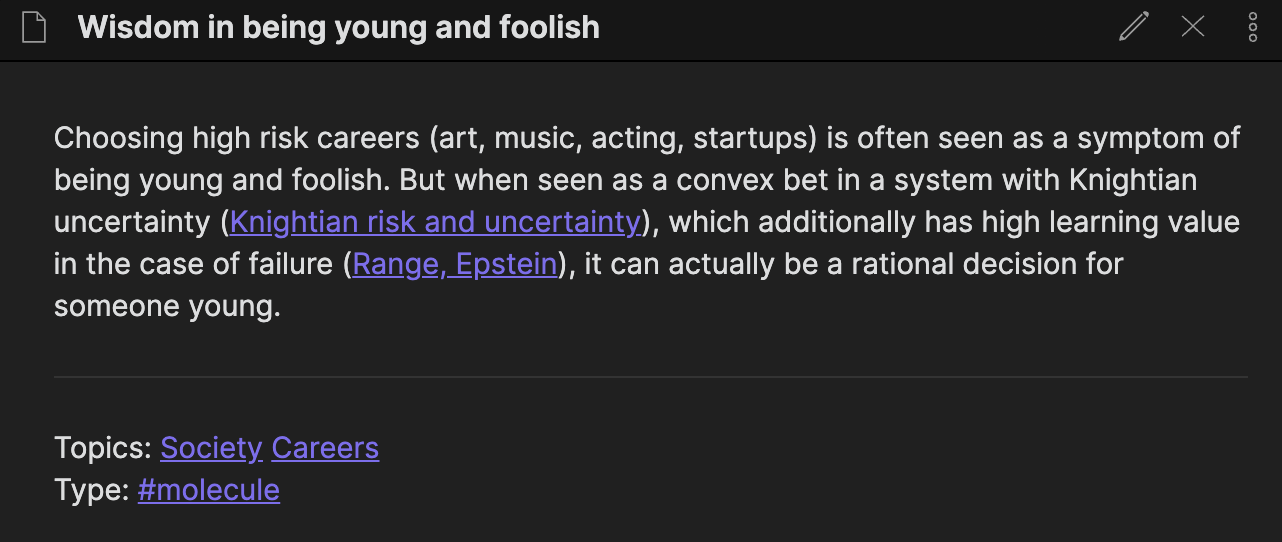

It’s difficult for me to explain what exactly a Molecule is. The best I can do: a Molecule is an insight. This insight should be self-contained and discrete (in the sense that it can stand on its own). My Molecules are typically only a couple of sentences – a paragraph at most. In most cases, a Molecule will “build on” one or more Atoms (which is why I called it a Molecule in the first place).

To be a little more concrete, here are several types of Molecules along with examples.

- Original insights I have, often inspired by some Source. (When I say “original”, I mean “originated by me”. I doubt any of my ideas are original in the sense that they haven’t been thought of before).

- Original insights I have, related to an Atom:

- Links between two Sources, e.g. when I notice that two Sources are talking about the same concept in different ways:

- Links between two Atoms:

- Intelligent pieces of commentary related to a Source:

All of the above examples are “original” ideas or links between several pieces of knowledge. However, Molecules don’t need to be original. Many of my Molecules are crystallised insights based on a Source: moments of clarity I’ve achieved after stumbling through the conceptual thicket. I make Molecules like these when I feel that I know exactly the point an author is trying to get across and I can explain it succintly in my own words.

- From Black Box Thinking by Matthew Syed:

- From Euan Sinclair’s textbook Volatility Trading:

- From Patrick O’Shaughnessy’s Invest Like the Best podcast, with guest Marissa King:

I will typically only make something a Molecule (rather than just a bullet point in the Source) if I feel like I have internalised the idea to the point where I would be comfortable calling it a piece of “my” intuition.

Summary – Molecules

Molecules are insights – either my own, or an insight I have internalised from a particular Source. Creating Molecules is the primary goal of Molecular Notes!

Topics

Along with the three primitives – Sources, Atoms, Molecules – Molecular Notes uses Topics (a.k.a categories) as an organising principle.

Categorisation is relatively controversial among note-takers. I want to briefly outline both sides of the debate.

The “spreadsheet” school of thought (my terminology) posits that the whole purpose of note-taking is to turn unstructured thoughts into something highly structured, presentable and reviewable (hence “spreadsheet”) – the more categorisation and organisation, the better. But many Second Brain apologists reject top-down categorisation (see e.g. Why Categories for Your Note Archive are a Bad Idea) in favour of emergent structure – they think that structure should emerge organically from the links.

I think the truth is somewhere between these two extremes: I think that both deliberate and emergent structure – categories and links – are useful. In my view, structure aids understanding because it allows me to build a better map of where a piece of knowledge belongs. Pure emergence (i.e entirely unstructured note-taking) makes it harder to revisit the content.

The problem with categories in traditional note-taking systems is that they often encourage a structure that is too rigid to support the concepts I am trying to learn. For example, in a traditional “files and folders” note system, it is hard for a note to belong to several categories: you’d have to duplicate a file in multiple folders, which seems wasteful. This leads to the “Categorisation paralysis”: when the inability to decide where to categorise some knowledge reduces efficiency (I am reminded of this scene in Wall-E, as he struggles to categorise a spork).

But in modern software, this concern melts away. The way I use Obsidian, categories are merely empty notes that I can link to: I can link to as many categories as I would like. For that reason, I typically think of these as Topics rather than categories – “category” feels more exclusive, whereas “Topic” just means that there is a related subject.

The advantage of Topics is that they give structure to my Second Brain and help me figure out which area of my graph to hunt for a particular concept or link. If I’m learning something about statistics, I will often have a look at the local graph of the statistics Topic to see if there are any interesting links:

If over time, I see that a particular Topic isn’t useful to me (e.g. I later find it was too specific or too broad), I just delete it!

In Part 2, I will go into more detail about how exactly I organise my Second Brain: in particular, how I use Topics, folders, and tags.

Summary – Topics

Topics are a simple and flexible way of introducing structure to my Second Brain. They make it easier to search my Second Brain and to find possible links.

Why Molecular Notes matters to me

Generally I’m quite critical of “productivity YouTube”. The classic archetype is a YouTuber explaining some productivity tool when it’s clear that that they are mostly using the tool to administrate their YouTube videos – something that is presumably not applicable to the majority of viewers. Or a Zettelkasten video where the YouTuber’s three zettels are “Niklas Luhmann”, “Zettelkasten”, and “Linked thinking” – i.e they are using the zettelkasten system as a prop in a video rather than an actual note-taking system. Andy Matuschak puts it thus: “people who write extensively about note-writing rarely have a serious context of use”. Cedric C brings up a similar point regarding mental models (link): there are far more people who write about mental models than people who effectively apply mental models.

These concerns were a real barrier when it came to writing this blog post – the prospect of becoming a “productivity YouTuber” terrified me. Even as I write this, I realise that I’m still unable to clearly articulate what Molecular Notes enables me to do, though I unequivocally maintain that I’ve derived immense value from it.

I guess it comes down to this: to the extent that you think I’ve got interesting ideas or a thought-provoking blog, or you like the way I think about things, all of that has been significantly enabled by my Second Brain. Perhaps not originated by the Second Brain, but at least amplified. Subjectively, I was a keen learner even before using Second Brain and I was decent at spotting connections between different things I had read. But codifying my workflows into Molecular Notes has dramatically accelerated up my pace of learning, even given the constraints of adulthood. I’ll admit this is a weak explanation. I’m essentially saying that I like using my Second Brain because I think it makes me more productive – a highly subjective and vaguely circular argument.

To be slightly more concrete, Molecular Notes gave me a tangible benefit during my internship at a hedge fund (as it continues to do in my full-time job at the same hedge fund) because it allowed me to learn about highly technical areas quickly, while spotting the manifold links to related fields – trading is surprisingly interdisciplinary at the end of the day, drawing on mathematics, computation, psychology, statistics, and economics (among others). I would love to be more specific, but unfortunately the constraints of discretion prevent me from doing so. Nevertheless, the key point I’m trying to convey is that I believe Molecular Notes has helped me in practice. It isn’t just “blog material” – in fact, I only wrote this post after several people independently asked for it.

Who is Molecular Notes for?

Inevitably, Molecular Notes evolved around my particular needs and interests: it is different to the Zettelkasten and Evergreen note-taking systems because my needs are different to those of Luhmann and Matuschak, their creators. It thus stands to reason that what works for me may not work for you, so you should approach Molecular notes with the same philosophy I approached the existing note-taking systems: a source of inspiration; a basket of features, some of which may fit your use case.

I want to highlight several areas in particular where I think Molecular Notes is not well suited (without modification).

For students taking closed-book non-essay exams (particularly STEM subjects), I recommend using a note-taking system that better matches the exam format and treats spaced repetition as a first-class citizen. In my university programme, it was important for me to have all of the concepts and techniques at my fingertips and to practice applying them. Knowing about the concepts on a meta level (in particular, finding connections between different techniques) was not terribly important – perhaps this says something about the exam format! Obsidian does provide spaced repetition functionality via extensions, and as I will discuss in Part 2, I coded up my own little spaced repetition tool to work with Molecular Notes, but in truth I think you are better off with a dedicated spaced repetition tool like RemNote. It was specifically designed for spaced repetition and they have full-time developers maintaining and improving the functionality.

Secondly, while I think many of the ideas in Molecular Notes are highly relevant to academics – particularly the ability to look for connections across Sources – more emphasis would need to be placed on collating references from articles. In academic writing, it is sometimes useful to have verbatim quotes from another article, while in Molecular Notes this is rare. If one’s goal is academic writing, the original Zettelkasten system may be a better fit.

Lastly, Molecular Notes is entirely optimised for evergreen content, as opposed to tracking ongoing events or dealing with new situations (remember, my Second Brain is not a project management tool). In Part 2, I will discuss how Molecular Notes could be modified to address these applications.

Lay of the land – other note-taking systems

Molecular Notes is based on a lot of prior art. Having presented the principles of Molecular Notes, I want to compare and contrast it to two other related systems: Zettelkasten (the OG) and Evergreen notes.

Perhaps after reading this section, you will feel that one of those is a better fit for you. As far as I’m concerned, that’d be an excellent outcome! We must each find the tools that best suit our goals and learning style.

Zettelkasten

How to Take Smart Notes by Sonke Ahrens (my highlights here) may end up being the most important book I’ve read because it significantly accelerated my interest in note-taking systems, thus acting as a force multiplier on everything I’ve learnt since. In the book, Ahrens outlines Zettelkasten, a note-taking system used by the sociologist Niklas Luhmann. Zettelkasten, implemented in Notion, was my first “thoughtful” note-taking set-up – though my system later began to deviate for reasons discussed below.

There is so much about Zettelkasten online (this is a good starting point) that I hesitate to add to the noise. But for the sake of contrasting it with Molecular notes, the main primitives in the Zettelkasten system are:

- Reference notes: contain bibliographic information about a source, along with a brief summary of the source.

- Literature notes: a summary of a particular point made in a Source. When you read a Source, you will generate many separate Literature notes.

- Permanent notes (zettels): your insights.

Eva Keiffenham has a helpful diagram outlining the difference between literature notes and permanent notes in Zettelkasten:

If you would like to see a Zettelkasten system implemented in Obsidian, this video by Artem Kirsanov is the best walkthrough I’ve seen (be warned: many/most of the outlines of Zettelkasten on YouTube are mediocre at best).

The main reason I needed to evolve beyond Zettelkasten is that it lacks a good primitive to deal with established concepts. For example, let’s say I am learning about chemistry and I have just learnt about the Haber process to manufacture ammonia. This is important to my thinking, so I want to include it in my note-taking system. Zettelkasten would include this either as a literature note (referencing the textbook you’re reading) or in a permanent note. But neither seems ideal. If it’s in a literature note, then when I read another textbook with a slightly different discussion of the Haber process, am I going to have a separate literature note for it? Putting it in a permanent note (explained in my own words) makes more sense, but it feels weird to put a “known” concept with an unoriginal explanation into the Zettelkasten.

Secondly, many aspects of Zettelkasten arose out of the physical medium that Luhmann used (literal slips of paper in boxes). The decision to have Literature notes as separate individual notes makes sense in the context of physical slips of paper (writing a large document would make it hard to restructure), yet in a digital system I think it’s much easier to have all of my notes (or at least pointers to notes) from a given Source in one document. Luhmann’s original Zettelkasten also uses a nontrivial naming convention to represent backlinks – something that is clearly unnecessary with a digital Zettelkasten.

We should remember that Luhmann devised the Zettelkasten system to be a more productive sociologist. Sociology, as I understand it, largely involves the analysis of different qualitative theories – it deals with a smaller body of known facts/concepts and a larger body of qualitative discussion (this is not meant to denigrate sociology in any way). For STEM subjects, on the other hand, there are textbooks full of known concepts and techniques. I want to learn when to use these concepts and how they all connect – Zettelkasten is not naturally suited to this.

Evergreen Notes

Evergreen Notes is a system developed by Andy Matuschak, similar in many ways to Zettelkasten. Maggie Appleton has a nice visual explainer, but the ground truth is surely Matuschak’s own writing on the topic. If you are interested in note-taking, this is an absolute must read – I suggest you set aside an hour to trawl through his insights. I arrived at many of the same ideas independently, but I would have saved many hours had I simply read his thoughts to begin with.

I agree with most of what Matuschak writes, but there are a couple of areas where his system didn’t quite work for me.

Firstly, there are no Source notes. As Matuschak explains, his system is designed to optimise for creative thought rather than ingesting other peoples’ ideas so there isn’t a great way to take linear notes on a textbook, for example. I’m sure this is valid for someone as erudite as Matuschak, but given where I am in life’s learning curve, it’s very important to me that I have a good system for taking notes on educational resources.

Secondly, he doesn’t use categories of any kind (this criticism applies to Zettelkasten as well). He explains this in a delightfully-titled permanent note “Prefer associative ontologies to hierarchical taxonomies”, but for the reasons I described earlier, I think categories (Topics) are a good way to index my knowledge.

Following on from the above, the lack of structure makes his system (at least the public version) very hard to navigate, especially since it lacks search functionality and a graph view. Matuschak himself points this out.

Summary – Molecular Notes in context

I don’t want to overstate the novelty of Molecular Notes: it was heavily inspired by Zettelkasten, and incorporates many of Matuschak’s innovations (though most were arrived at independently).

The main additions of Molecular Notes that I feel aren’t well-captured by the existing systems:

- Good workflows for taking linear notes from some resource (Sources)

- Primitives for established concepts (Atoms)

- A top-down structure, albeit a flexible one (Topics)

Failure modes

A recurring theme of this post is that you should modify Molecular Notes to work for you. But before wrapping up, I want to outline some failure modes that you should take care to avoid!

- Categorisation hell:

- Don’t spend too much time trying to come up with a fancy categorisation scheme.

- Pick something simple and flexible – something that you can build on top of as you get a better understanding of your particular needs

- Completionism:

- Don’t add irrelevant things to your Second Brain.

- It can be tempting to try and be comprehensive but this leads to notes that are harder to review

- Not every concept deserves its own note!

- Complicated metadata:

- Don’t try to overcomplicate the metadata – when I create a new note I only need to put three fields: “Topics”, “Reference” and “Type”.

- Anything complicated starts to be a barrier to creating notes.

- Copy-pasting content:

- Copy-pasting is a no-go: it defeats the purpose of a Second Brain.

- Further, it dramatically reduces retention while simultaneously encouraging completionism

- Not being intentional about note-taking:

- Don’t slip into autopilot and make traditional notes!

- Molecular Notes requires you to actively engage with the content, restructure old Sources even as you’re consuming a new Source, and constantly be on the lookout for opportunities to link ideas.

Conclusion

Part 1 of the series has outlined my objectives for a Second Brain system and proposed Molecular Notes to address them.

I apologise if this post has been excessively abstract. In Part 2, the pendulum will swing the other way as I present my actual Obsidian setup in a sickening amount of detail. You have been warned!