Intuiting the gamma function, part 2

In Part 1, we showed that repeated differentiation gives rise to a factorial. In this second post of Intuiting the gamma function, we are going to show that integration by parts can also produce a factorial – an instrumental step in generalising the idea of a factorial to non-integers.

Just a couple of minor points regarding the presentation of this post. I will abbreviate ‘integration by parts’ to IBP, since we will be mentioning it rather often. I will also consistently exclude the constant of integration, because it is just clutter.

A quick IBP refresher

If we are integrating a function $f(t)g’(t)$, the IBP formula tells us:

\[\int fg'dt = fg - \int f'g~dt\]Notice some things:

- There is both differentiation and integration involved. $f(t)$ is differentiated, while $g’(t)$ is integrated.

- There is a minus sign, which will later be very important.

As we saw in the previous post, in order to end up with a factorial, we will have to repeatedly differentiate something like $x^n$. As such, I am going to let $f(t) = t^n$. This is because $f(t)$ is always differentiated in the IBP formula.

We also need to choose a $g(t)$, which will be always be integrated. I will choose the exponential function because it stays the same and makes everything easier. Maybe you think that I’m just choosing it because I know for a fact that the gamma function includes an exponential, but even if you think so, I urge you to read on as this doesn’t affect the intuition behind the gamma function – it just makes this post an explanation instead of a derivation.

A shortcut for repeated IBP

It may not be clear what I am trying to say at first, but it will make the eventual moment of understanding that much better. Follow along with the steps for now, and hopefully I will be able to make it all come together.

Consider the integral $\int t e^t dt$. We set up the parts required:

\[\begin{aligned} f = t \implies f' = 1\\ g' = e^t \implies g = e^t \end{aligned}\]Now we apply the IBP formula:

\[\begin{aligned} \therefore \int t e^t dt &= te^t - \int e^t dt\\ &= te^t - e^t \end{aligned}\]What about $\int t^2 e^t dt~$? We can still use IBP, though we have to do it twice. The first time:

\[\begin{aligned} f_1 = t^2 \implies f_1' = 2t\\ g_1' = e^t \implies g_1 = e^t\\ \therefore \int t^2 e^t dt = t^2e^t - \int 2te^t dt. \end{aligned}\]We already know what $\int te^tdt$ is, so we conclude that:

\[\int t^2 e^t dt = t^2e^t - 2te^t + 2e^t\]Look carefully at the structure of the above answer. What can you notice? First, there is an alternating sign between each term. Secondly, each term is made up of a differential and an integral. For example, in $t^2e^t - 2te^t + 2e^t$, notice how the first part of each term is the derivative of the previous term’s first part ($t^2 \rightarrow 2t \rightarrow 2$).

These two facts aren’t just coincidences, they are a direct result of the IBP formula: the $f(t)$ that we choose is always differentiated and the $g(t)$ is always integrated. The alternating sign between the terms is explained by the fact that there is a minus sign in the IBP formula, so when we apply the IBP formula multiple times, some of the negative signs cancel to become positives, while some stay negative.

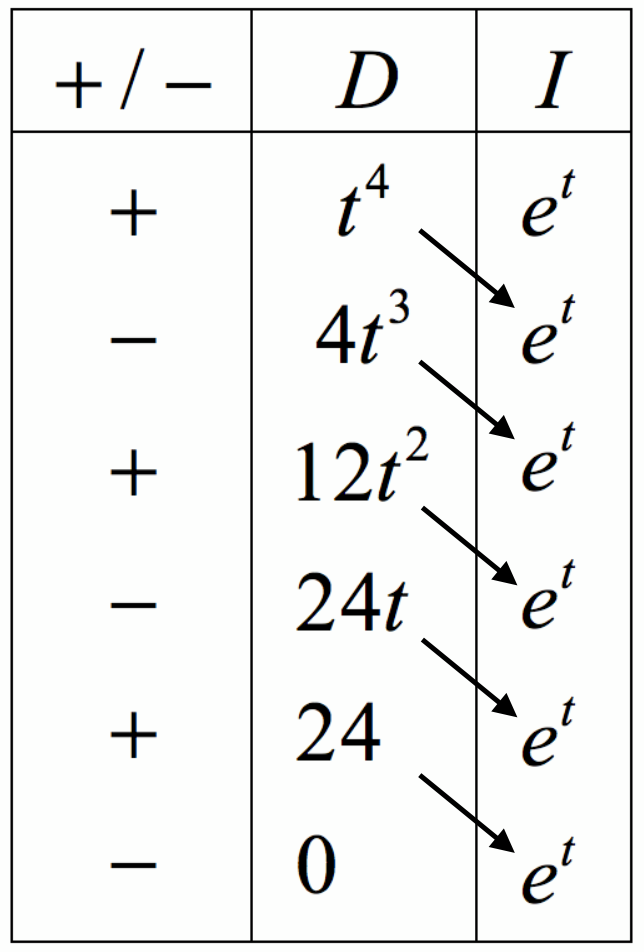

In fact, we can derive a useful shortcut from this. Let us now try to evaluate $\int t^4 e^t dt$. This would normally be very tedious, as we would have to apply IBP four times! But let’s be clever about it. The integrand has two parts, $t^4$ and $e^t$. As we saw, the former will always be differentiated while the latter will always be integrated. Not forgetting the alternating signs, we can set up a small table:

The D denotes the part of the integrand which we will always differentiate, i.e the f that we choose for the IBP formula. Every term in the D column is the derivative of the term above it.

The I denotes the part of the integrand that we will always integrate, i.e the $g’$ that we choose. Every term in the I column is the integral of the term above it (this is why we chose $g’(t) = e^t$; it is easy to integrate).

The +/- column represents the alternating sign.

Combining these facts provides an easy shortcut to integrate by parts. We simply lattice multiply according to the arrows, and include the sign.

\[\therefore \int t^4 e^t dt = t^4e^t - 4t^3e^t -24te^t + 24e^t\]This is reminiscent of the Maclaurin expansion in the sense that we are differentiating a power of t many times. When we did that $n$ times, the result was a factorial. Could we apply the same logic here? Why don’t we just go ahead and evaluate $\int t^n e^tdt$?

A minor problem

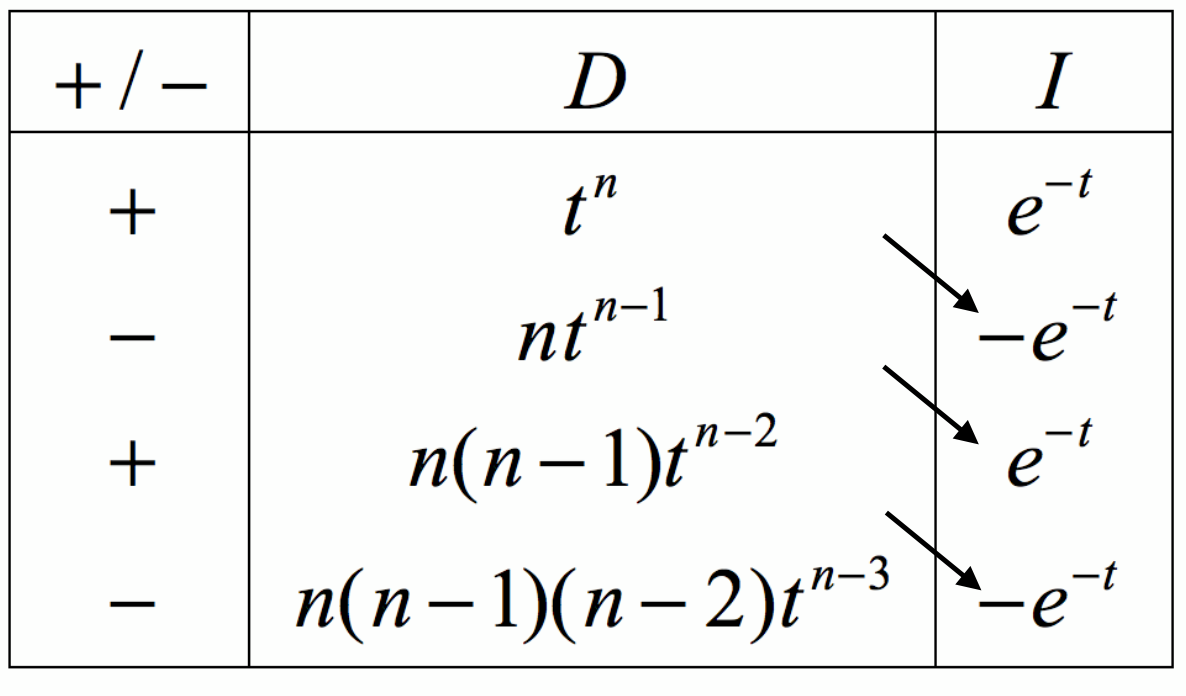

Due to the alternating signs in the first column of our table, we will not be able to properly evaluate the integral $\int t^n e^tdt$ – how would we know whether the nth term is positive or negative? However, there is an elegant workaround: we change our $g’(t)$ from $e^t$ to $e^{-t}$. Successive integrations of $e^{-t}$ have alternating sings, so when we multiply out with the alternating signs in the first column of our table, they will all cancel so that everything will be negative!

To show this clearly, consider the table to evaluate $\int t^n e^{-t}dt$:

Lattice multiplying the first few terms gives

\[t^n(-e^{-t}) - nt^{n-1}e^{-t} + n(n-1)t^{n-2}(-e^{-t})-\ldots\] \[= -t^ne^{-t} - nt^{n-1}e^{-t}-n(n-1)t^{n-2}e^{-t}-\ldots\]Every term has a negative sign, because we have two sets of alternating signs that cancel to a negative! Because we know that all the terms are negative, we can proceed.

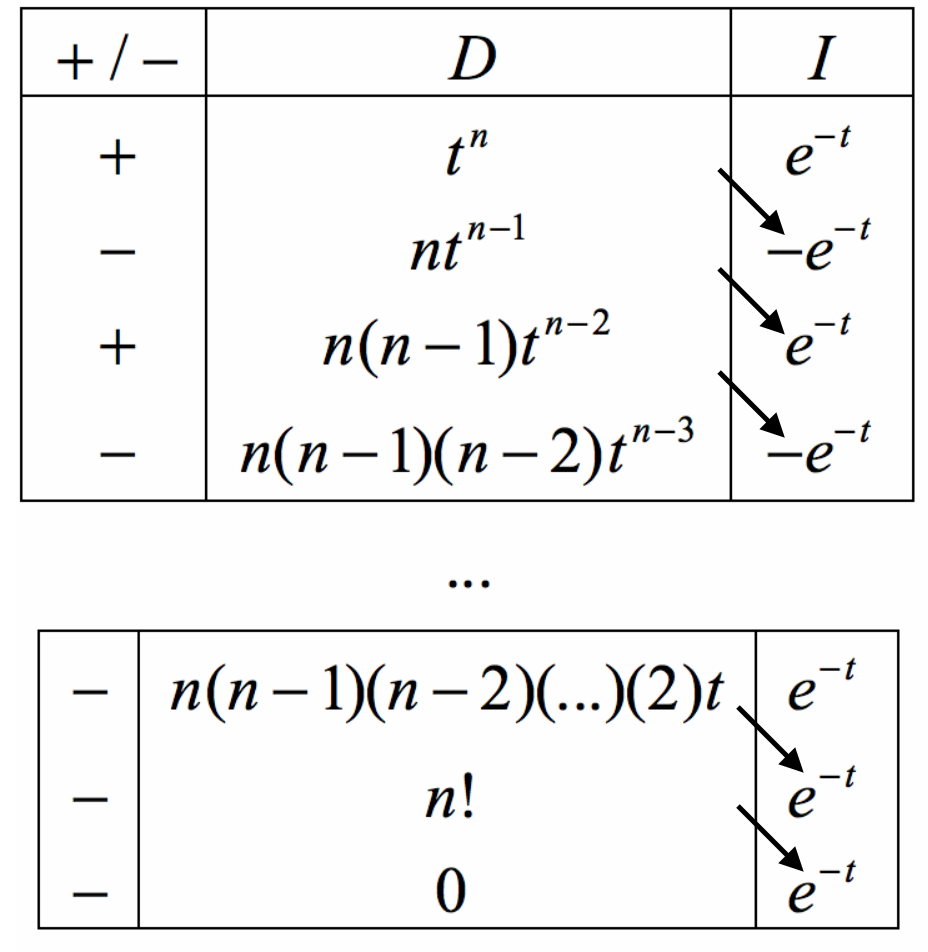

Integrating by parts n times

We will now evaluate $\int t^ne^{-t}dt$:

Thus we see that:

\[\begin{multline*} \int t^n e^{-t}dt = -t^ne^{-t} - nt^{n-1}e^{-t}-n(n-1)t^{n-2}e^{-t}-\ldots \\ - n(n-1)(n-2)(\cdots)(3)(2)te^{-t} - n!e^{-t} \end{multline*}\]Note very carefully the last term – we have managed to produce an $n!$ (I would put another exclamation mark there, but…)

This is good news, but we now need to isolate the $n!$ by removing all of the other terms. The easiest way to do this is to cleverly choose limits on our integral such that all of the other terms, as well as the $e^{-t}$ in $-n!e^{-t}$ disappear to leave us with solely $n!$

To do this, we can first notice that if the lower limit of the integral were zero:

- all of the terms that contain powers of x will disappear (since anything multiplied by zero is zero)

- the last term would reduce to $n!$ because $e^0=1$.

Hence choosing a lower limit of 0 produces $n!$ and nothing more. Wouldn’t it be great if we could now choose a suitable upper limit that will make all other terms disappear? This can be done. Note that as t grows, $e^{-t}$ shrinks. In particular, as $t \rightarrow \infty$, $e^{-t} \rightarrow 0$. Thus if our upper limit where $\infty$, every single term would equate to zero. Just what we need, since our lower bound has already produced $n!$ Adding these limits to the integral:

\[\begin{aligned} \int_0^\infty t^n e^{-t}dt = \left[ -t^ne^{-t} - nt^{n-1}e^{-t} - \ldots - n!te^{-t} - n!e^{-t} \right]_0^\infty\\ = [0] - [-n!] = n! \end{aligned}\]By using our well-chosen limits, we have produced a factorial (and nothing more). To reiterate:

\[\int_0^\infty t^n e^{-t}dt = n!\]This is a hugely significant result, as we have shown that the factorial can be written as the result of an integral. But integrals don’t have to have integer components – we have managed to de-couple factorials from integers, which is what we set out to do! We shall therefore redefine the factorial, and change the variable from n to x to reflect the fact that we don’t just have to deal with integers any more:

\[x! = \int_0^\infty t^x e^{-t}dt\]Doesn’t this look familiar?

Conclusion for part 2

We have shown that repeated integration by parts can produce a factorial, and in fact that

\[x! = \int_0^\infty t^x e^{-t}dt\]Compare this to the gamma function, and you will see that there is only a slight difference:

\[\Gamma (x) = \int_0^\infty t^{x-1}e^{-t} dt\]The first integral has an $x$ in the exponent, while the second has an $x-1$. You can connect the dots here on your own, but in Part 3 I will explicitly show how the gamma function related to the factorial.