Rebuilding PyPortfolioOpt: an open source adventure

A few weeks ago, a user raised an issue on the GitHub repository for PyPortfolioOpt, my open-source portfolio optimisation software library. In this nontechnical post, I discuss why a seemingly innocuous error resulted in a ground-up rebuild of a large chunk of PyPortfolioOpt, and share some reflections on open-source in general.

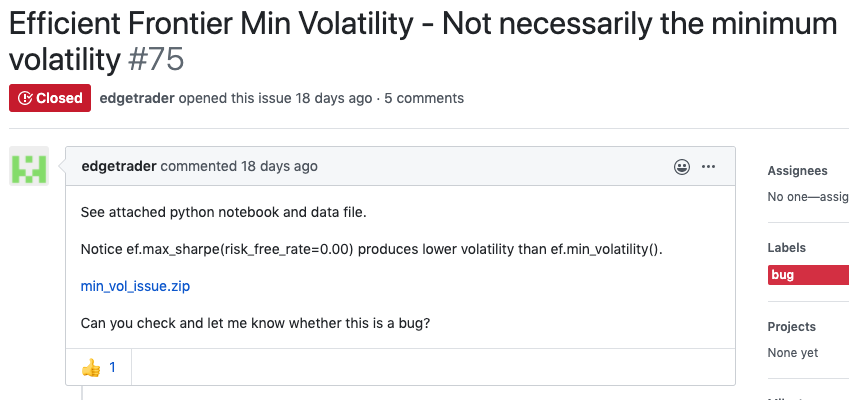

The actual bug that was reported is not particularly important, but it is quite easy to explain. PyPortfolioOpt offers a piece of functionality to construct a portfolio with minimum volatility (i.e minimal risk) – aptly called min_volatility. The problem was that it wasn’t working. One of my users, going by the name edgetrader, had provided a sample dataset and some code, which he claimed was producing incorrect output. I hate to say it, but issues like these are often caused by the user not formatting the data correctly or using the wrong value for a parameter. However, edgetrader’s code looked fine, and running it on my machine did nothing but confirm the issue – min_volatility was failing to produce the minimum volatility portfolio (for a painfully simple dataset too!).

I had a very good guess of where the error was coming from (later confirmed by another GitHub user, gatorliu). It was as bad as it could possibly be. To use an automotive analogy, rather than being a minor issue with an indicator light or windscreen wiper, the problem here was coming from deep within the engine. In PyPortfolioOpt, this corresponds to the backend optimiser – the part of the package that does the mathematical legwork of actually crunching the numbers to optimise a portfolio.

What is a backend?

The terms “frontend” and “backend” are often thrown around within the software engineering space, so let’s clarify exactly what we mean. In this context, I think of PyPortfolioOpt as being split into two broad chunks: the “frontend” API (application-programmer interface), i.e how users interact with the software, and the “backend”, which is the part that actually solves the optimisation problem. In the car analogy, which we will continuously revisit, we might say that the frontend API is the steering wheel, gear stick, pedals, etc. (whatever the user is interacting with), while the backend is what goes on “under the hood” (engine, transmission, electronics).

Now, as mentioned before, the “engine” of PyPortfolioOpt is the optimiser. Generally, optimisation is a very difficult mathematical task; many PhD-holders are paid a lot of money to build software routines for optimising different functions under different scenarios. For an open-source project (especially one not directly related to numerical computing), the norm is to pick from a handful of open-source optimisers, which, to be absolutely clear, have also been developed by extremely talented people. The problem is that it is rather difficult to decide on which one. So I put it to you – you have three choices:

- A general-purpose optimiser that can optimise for all different kinds of user objectives and constraints, with a very simple syntax.

- An optimiser that is highly specialised for a certain type of optimisation problem (which includes financial portfolio optimisation), but is not very flexible to user constraints, and requires strong mathematical competence to interact with.

- An optimiser that builds on top of choice #2, which provides a much nicer interface.

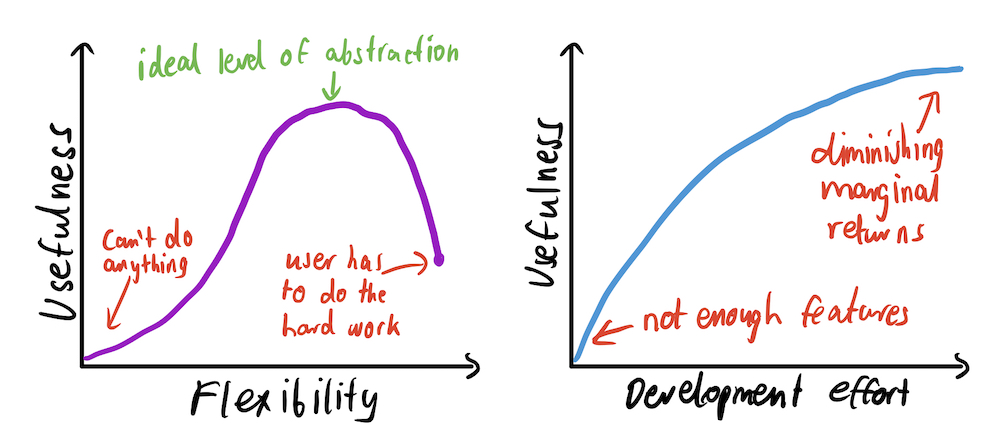

What would you do? Bear in mind that it’s only really feasible to choose one and that it will take a large amount of development effort so the cost of swapping is very high. One further point is that although in theory, we like to treat the frontend API and backend as completely separate, your choice of backend will inevitably impact what the frontend looks like.

Technical debt

In March 2018, when I first started building PyPortfolioOpt, the choice seemed like a no-brainer. I chose the first option, which corresponds to scipy. A flexible optimiser that can work with all sorts of user objectives? Sounds fantastic! However, even then I knew that I was making a tradeoff; as I said, optimisation is a tough problem, so while option #1 in principle works with many different kinds of optimisation problems, it is actually less likely to produce the true optimal solution (it might, for example, get stuck in a “good” but suboptimal solution).

Contrast this with #2, which is a package called cvxopt. cvxopt is an efficient solver for convex optimisation problems (the definition of ‘convex’ doesn’t matter here; all you need to know is that it is a narrow subset of all possible problems). Luckily, portfolio optimisation is a convex problem, at least with standard objectives and constraints, so it should produce much better solutions. With that in mind, why did I choose scipy? Here are a couple of reasons:

-

The syntax for

cvxoptwas much harder to understand and required a greater level of mathematical sophistication (in March 2018 I hadn’t started university so I was somewhat constrained in that regard). Here’s a quick example to illustrate the difference between syntaxes – note how it is quite clear what everything is doing inscipy, whereas forcvxoptyou have to be quite familiar with the library and the mathematical formulation of the problem:# Option 1: scipy result = scipy.optimize.minimize( fun=volatility_objective, args=(cov_matrix,) x0=np.ndarray([1/n] * n), bounds=[(1, 0), * n] constraints=[{"type":"eq", "fun" lambda w: np.sum(w) - 1}] ) weight = result["x"] # Option 2: cvxopt G = cvx.matrix(0.0, (n,n)) h = cvx.matrix(0.0, (n,1)) A = cvx.matrix(1.0, (1,n)) b = cvx.matrix(1.0) result = cvx.qp(mu * cov_matrix, -ret, G, h, A, b)['x'] - I didn’t think the performance different would matter very much.

- I was lazy.

I think you’d agree that the first two reasons seem fair; the third merits more of a discussion.

Technical debt is a very important concept in software development, be it open-source or in business. It is the idea that by choosing “quick and easy” solutions that seem to meet your needs now, you incur a debt that will eventually need to be repaid once your product reaches a certain stage of growth. While it has negative connotations, it is not always a bad thing. In the same way that large companies might borrow money to invest in a new project, incurring technical debt can be a great way to get your software up and running. This is a fundamental tenet of the Lean Startup methodology, according to which the most common reason why startups (and open-source projects) fail is that they spend a lot of time architecting a perfect solution to a problem that nobody has. To that end, it is critical to get a “minimum viable product” out the door as soon as possible so you can start receiving user feedback and iterating. Perhaps this is my way of rationalising a lazy choice, but given my constraints, I think it was probably the right decision at the time.

I released the first version of PyPortfolioOpt in May 2018 and received a strong positive response from the community, with surprising organic growth. Before long, it had a couple of hundred GitHub stars and surpassed most of the existing portfolio optimisation libraries. I believe this success was almost entirely due to the strong emphasis I placed on having an intuitive frontend API design and very detailed documentation, making it very easy for people to get up and running with the library. I did implement some semi-novel mathematics, for example, adding certain constraint functions to produce more diversified portfolios and creating new risk models, but this wouldn’t have mattered if the API were difficult to use.

One thing I did not anticipate was an influx of professional users, who were applying PyPortfolioOpt to real portfolio allocation problems. I had assumed that most professionals would use advanced in-house optimisation suites, but it turns out that there are many discretionary fund managers who were looking for a way to start systematising their allocation process and PyPortfolioOpt happened to come in at the right level of abstraction. For example, a typical workflow in PyPortfolioOpt is:

S = risk_models.sample_covariance(prices)

rets = expected_returns.mean_historical_returns(prices)

ef = EfficientFrontier(rets, S, weight_bounds=(0, 0.3))

weights = ef.min_volatility()

This requires a rough knowledge of what is going on (which most investment professionals have) but abstracts away all of the mathematics.

However, from the more quantitatively-inclined users (for example on the algotrading subreddit), I receive repeated (constructive) criticism on one area in particular – the use of the scipy optimiser on the backend. Many people shared their negative experiences with scipy and suggested I migrate to cvxopt. I took note of this feedback, but remained unconvinced that there was a significant performance difference, and decided to focus on building new features rather than working on the optimisation backend.

The tipping point

The issue that edgetrader raised was ultimately a strong impetus to completely re-evaluate my decision regarding the choice of the backend optimiser. Here I was, confronted with an astoundingly simple example (there were no weird constraints or objectives) for which the existing scipy backend was failing miserably. I could no longer credibly make the case that the worse performance was outweighed by the cleaner syntax, particularly with the thought that my library was being used to allocate real money.

I decided that it was time to “grow up”, and move on from scipy. But where would I go? I still disliked the cvxopt syntax and didn’t feel it was suitably extensible to provide my users with enough options. Additionally, although I was willing to make a few breaking changes to the frontend API (i.e changes that aren’t backwards compatible), I wanted to minimise this when possible, particularly for the basic user.

You may notice that after initially describing the three different options for a backend optimiser, I associated option #1 with scipy and option #2 with cvxopt. What about the last option?

An optimiser that builds on top of choice #2 [

cvxopt], which provides a much nicer interface.

I didn’t elaborate on it further because in March 2018 I didn’t think such a thing existed. However, I recently came across a library that got me truly excited – a viable alternative to cvxopt that provided a fantastic interface which I could weave into PyPortfolioOpt. The library is called cvxpy, a modelling language for convex optimisation problems courtesy of the clever folks at Stanford. There are two aspects of cvxpy that instantly sold me. Firstly, the syntax is wonderfully expressive:

w = cp.Variable(n)

risk = cp.quad_form(w, cov_matrix)

prob = cp.Problem(objective=cp.Minimize(risk),

constraints=[cp.sum(w) == 1, w >= 0])

Secondly, while cvxpy is restricted to convex optimisation problems, it has an incredible type-checker that can actually explicitly verify if a problem is convex and noisily fail if not. “Noisy failure” sounds terrible, but in fact, it is a gift for a developer – the reason being that if you know there is an error, you can programmatically fix it or make suggestions to the user. By contrast, the bug that edgetrader raised was a silent failure. The only way we found the bug was by manually checking the output.

The actual migration

Having decided to make the switch from scipy to cvxpy, it was time to rearchitect the project. People unfamiliar with the industry jargon sometimes find “software architecture” to be a curious phrase. In this context, it just means thinking at a high level about how all of the parts will interact with each other before actually coding it up – in the same way that architects design buildings before actually laying down the bricks.

I mentioned that I initially wanted to keep the changes entirely backwards compatible, so it would just be swapping out the engine while keeping the cockpit identical. However, when thinking about the architecture and reading cvxpy’s documentation, I realised that this would be incredibly limiting. One of my major goals with PyPortfolioOpt from day one was to have a highly modular design – that is, all the optimisation objectives are kept in one place, risk models in another, optimisers again elsewhere. This makes the codebase much simpler to understand, test, and build on, but more importantly, it allows for advanced users to swap in certain parts of the pipeline according to their own expertise. For example, if you are an investor who has a great model for predicting the expected returns of stocks, you should be able to plug that into the PyPortfolioOpt pipeline with all the other steps taken care of. The thoughtful design of cvxpy allowed PyPortfolioOpt to achieve the truly modular structure I always wanted. See if you can spot the lego bricks in the following example:

ef = EfficientFrontier(returns, cov_matrix, weight_bounds=(0, 0.3))

ef.add_objective(transaction_cost)

ef.add_constraint(lambda weights : weights[2] <= 0.05)

weights = ef.min_volatility()

Ultimately I felt that this modularity was well worth making a breaking change to PyPortfolioOpt. A major consideration was that cvxpy also provides a much better platform for future development effort. I suppose this was the foresight that I was lacking when I initially decided to use scipy on the backend.

All told, the actual migration went rather well. It’s always quite stressful to make breaking changes to the core part of a library because you have to have a very good idea of the interdependence between different parts of a project – even though I am the sole author, this is quite a task! However, two things in particular were an absolute blessing, and I would strongly advise other open-source developers to take note.

Firstly, documentation. The documentation is the “User Manual” which should detail how everything works. It may sound silly, but whenever a user asks me a question about PyPortfolioOpt, I normally don’t know the answer off the top of my head and end up relying heavily on the docs. “Self-documenting” is a popular myth; even in-line comments are not a suitable replacement for proper dedicated (separate) documentation. No user should have to dig through your source code to figure out how to use something.

Secondly, at the risk of saying “eat your vegetables”, having a comprehensive suite of automated tests made things so much easier. I wrote tests for PyPortfolioOpt mostly because it was “suggested best practice”, but they are truly an incredible resource when it comes to software development. Since each piece of functionality is independently tested, I no longer have to maintain an exact mental map of all of the details of the package. If I make a change in one place that happens to affect another function, you can be sure the tests will greet me with an angry red cross. An especially useful practice has been building new tests after every bug fix – for example, in PyPortfolioOpt v1.0.0 the tests include edgetrader’s bug, so we can both be sure it is well and truly resolved.

Conclusion

One thing that I want readers to take from this post is that software design, as with many things in life, is a game of tradeoffs.

You have to make a multitude of decisions (some small, some critical) about the frontend API, the set of features, backend design, etc. Doing this correctly results in a package that people actually enjoy using, leading to organic growth by referrals. Otherwise, you end up putting a lot of effort into something that nobody will use.

I realise that this post has made a lot of use of the ‘perpendicular pronoun’, whereas the truth is that I am indebted to the many contributors who have lightened my load by providing a steady flow of feedback, second opinions, feature suggestions, and code reviews. A special shoutout to Felipe Schneider, who often responds to issues much faster than I and has been indispensable when it comes to bug/feature triage and architecture suggestions.

PyPortfolioOpt is a living thing now, and we are well beyond the days when I can make whatever changes I like. PyPortfolioOpt is being used by real people to allocate real money, and to that end, I have a responsibility to develop responsibly, with a thought to both future progress as well as backwards compatibility. To my current users, I ask for your forgiveness. I can personally attest to the hassle of having to change your code because another library changed its interface. Please know that the change was made with performance and long-term usability in mind.

Having released version 1.0.0, I won’t be making any breaking changes for the foreseeable future. It is my hope that the recent bout of “creative destruction” has laid the groundwork for PyPortfolioOpt to continue a steady and sustainable growth trajectory, and maintain its position as the “go-to” python portfolio optimisation library.