Game Theory – Yale (Econ 159)

The course, lectured by Professor Ben Polak, can be found on YouTube or on the Open Yale Courses page.

- Introduction

- Iterative deletion

- Nash equilibria

- Mixed strategies

- Evolutionary stability

- Midterm

- Sequential games

- Imperfect information games

- Repeated games

- Asymmetric information

Introduction

A game requires a number of components:

- Players, denoted by $i, j, \ldots$ (there are N players)

- Strategies:

- $s_i$ denotes a particular strategy of player i, within a set $S_i$ of possible strategies.

- s is a particular play of the game (i.e every player’s choice of strategy). This is also known as a strategy profile.

- Payoffs, which depend on the strategy profile:

- $u_i(s) \equiv u_i(s_1, s_2, \ldots, s_N)$

- initially we will assume that these are all known by every player.

- It can be useful to think about the strategy profile (and payoff) in terms of player i’s choice combined with every other player’s choice. We use $s_{-i}$ to represent the latter, such that the payoff to player i is $u_i(s_i, s_{-i})$

- In simple two-player game, a payoff matrix is a complete description of the game, encoding the payoffs that you and your opponent receives for combinations of your actions (row headers) and their actions (column headers).

Game theory investigates how we can choose between different strategies:

- Strategy $\alpha$ strictly dominates strategy $\beta$ if the payoff from $\alpha$ is strictly greater than the payoff from $\beta$ regardless of opponents’ choices.

- i.e $s_i’$ is strictly dominated by $s_i$ if $u_i(s_i, s_{-i}) > u_i(s_i’, s_{-i}), \forall s_{-i}$

- NEVER play a dominated strategy

- likewise, assume your opponent will never play a dominated strategy.

- In the case of weak domination, the payoff from $\alpha$ is at least as high as payoffs from $\beta$, but is strictly higher for at least one of the other player’s choices.

- $u_i(s_i, s_{-i}) \geq u_i(s_i’, s_{-i}), \forall s_{-i}$ and $u_i(s_i, s_{-i}) > u_i(s_i’, s_{-i})$ for some $s_{-i}$.

- Rational play can lead to Pareto inefficient outcomes. Examples:

- classic Prisoners’ Dilemmas

- price competition in a duopoly – each incentivised to undercut even though this will lead to collectively lower margins

- common resources – incentive to overfish.

- Prisoners’ are not just a failure of communication. You would need to change the payoffs, e.g. by having contracts, or by playing repeated games.

An important meta-parameter is how skilled your opponents are at playing games (i.e their rationality)

- It is important to consider your opponents’ level of rationality, but also their belief of your rationality, their belief of your belief of their rationality, ad infinitum.

The limiting case, in which you know something, you know that they know something, you know that they know that you know something… is called common knowledge

- different from mutual knowledge – it is possible for both of you to know something, but not know if the other person knows it.

- this is the key to the “2/3 game”. You have to estimate the group’s rationality, and the group’s view of the group’s rationality, etc.

Iterative deletion

-

Since you shouldn’t play a dominated strategy (and you know your opponent won’t either), you can delete dominated strategies from the strategy set. But now that the game has changed, there may be new dominated strategies. These should be deleted again, and so on. This process is called iterative deletion.

- In a simple model of politics, we have a continuum of 10 stances on the political spectrum, from the left to the right.

- assume voters are uniformly distributed along the spectrum, and they will vote for the nearest candidate (in case of tie, split equally)

- the objective of the two candidates (players) is to maximise their share of the vote by choosing a position on the spectrum

- Position 1 is strictly dominated by position 2, because regardless of what the opponent does, position 2 captures more vote-share than position 1 would.

- Position 2 is not dominated by position 3 (because if opponent plays 1, position 2 is better off), but if we first delete position 1 (since it is strictly dominated), then position 3 does dominate position 2.

- We can then apply iterative deletion (and likewise from the 10/9 end by symmetry), such that the remaining strategies are the two centre strategies at 5 and 6. This is the median voter theorem.

- We observe the same phenomenon in product placement (similar shops cluster together).

Nash equilibria

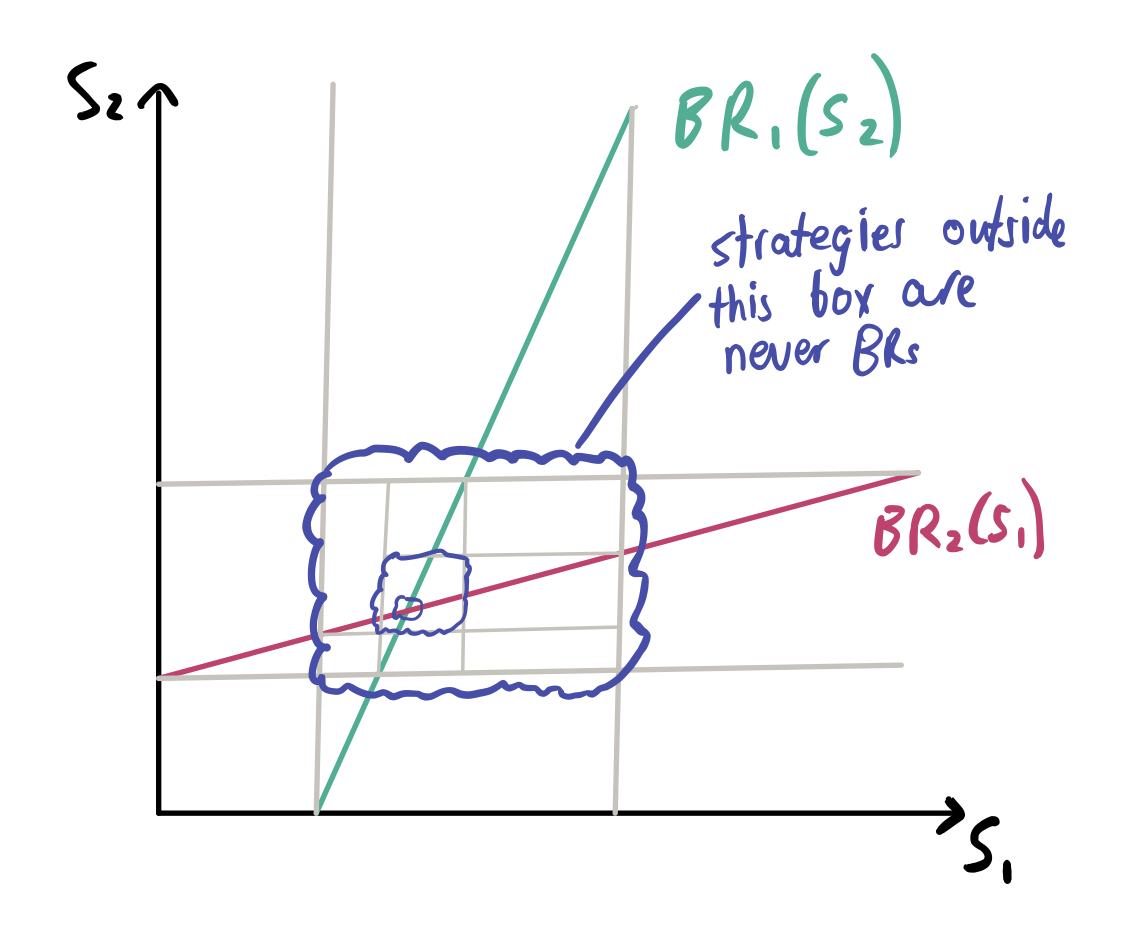

- Some strategies are never the best responses, regardless of the opponent’s choices. These never-best response (NBR) strategies are not rationalisable.

- Hence we can also delete NBR strategies, not just dominated strategies.

- Formally, player strategy $\hat{s}_i$ is a best response to the strategy $s_{-i}$ of other players if $\hat{s}_i$ solves $\max_{s_i} u_i (s_i, s_{-i})$. Alternatively, we can frame this in terms of expected payoffs and beliefs about the other players’ choices.

- Assuming your strategy set is continuous, the best response to an opponent’s choice can be found by differentiating the payoff function with respect to your strategy, to find the strategy that maximises payoff.

- in a two player game, this gives $\hat{s}_1$ as a function of $s_2$ and $\hat{s}_2$ as a function of $s_1$.

- we can use iterative deletion of NBR strategies. For some games, this converges to a single value.

- The point of convergence is called a Nash Equilibrium (NE) - when each player is playing a best response to each other.

- formally, a strategy profile is a NE if, for each i, the player’s choice $s_i^*$ is a best response to the other players’ choices $s_{-i}^*$.

- no individual can do strictly better by deviating (holding others fixed) – no regrets.

- related to the idea of self-fulfilling beliefs. It can be the case that if you believe your opponent will do something and intend to act on that belief, your opponent will now act that way (even if they normally wouldn’t).

- No strictly dominated strategy can be part of a NE (by definition). However, weakly dominated strategies may be part of a NE:

- in the game below, both the bottom-right is part of the NE – no player can do strictly better by deviating.

- however, strategy a dominates strategy b

a b a 1, 1 0, 0 b 0, 0 0, 0

Coordination games

- NEs are typically easy to find via guess-and-check, as long as the strategy sets are small (even if there are many players). In the Investment Game, players can either choose to invest \$10 or not invest. If more than 90% of the class invests, you make \$5 profit. Otherwise, you lose your investment.

- there are two NEs: everyone invests or nobody invests. However, the Pareto dominant strategy is for everyone to invest.

- play may converge to NEs if games are played repeatedly.

- games with multiple NEs can be coordination games, in which case everybody does better off if you can coordinate (Unlike Prisoner’s Dilemma, where there is a strictly dominated strategy).

- communication can help! NE can be self-enforcing agreements. You don’t need to change the payoffs with a contract/regulator to change behaviour.

- there is scope for leadership to improve outcomes.

- Another example of a coordination game is the Cournot duopoly, which models a 2-firm market that is neither perfectly competitive nor perfectly cooperative.

- each firm produces identical products $q_1, q_2$ with constant marginal costs $cq$.

- the more the firms produced, the lower the price: $p = a - b(q_1 + q_2)$.

- each firm aims to maximise their profit $u_1(q_1, q_2) = q_1(p-c)$, i.e revenue - cost.

- the best-response curves are straight lines between the monopoly quantity and the competitive quantity (quantity at which price equals marginal cost)

- In Bertrand competition, firms set prices rather than quantities (they provide as much quantity as there is demand for).

- it can be shown that the unique NE is $p_1 = p_2 = c$

- i.e perfect competition is achieved with only 2 firms.

- this disagrees with the Cournot model. However, differences are explained if we relax the assumption that products are identical.

- Strategies are called strategic complements if they mutually reinforce one another, or strategic substitutes if they mutually offset one another. Strategies in the investment game are strategic complements.

- strategies in the investment game are strategic complements – if other people are investing, you also want to invest

- the Cournot duopoly shows strategic complements

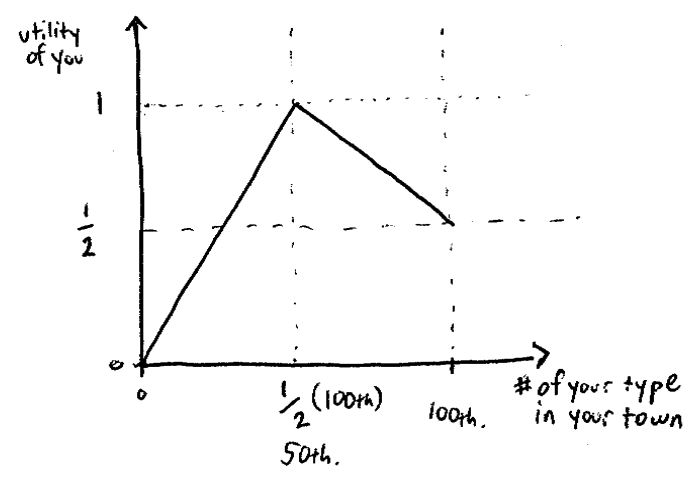

The Candidate-Voter model

- Model an even distribution of voters on the unit real line, with voters voting for the closest candidate.

- However, unlike the previous situation:

- each voter is a potential candidate. They can choose to run or not to run.

- number of candidates is endogenous

- candidates cannot choose their position – everyone can look at track records to know if you are Left/Right.

- there is a prize for winning B and a cost of running c, where $B \geq 2c$.

- if you are x and the winner is at y, you pay a cost equal to $-|x-y|$ because you don’t agree with the winner’s policy.

- If no candidates run, it isn’t an NE because someone’s best response is to run and win the election.

- If only one candidate, there is a NE for a centrist candidate and odd number of voters. But if there is an even number of voters, someone else would run as a candidate.

- With two candidates, there is a NE if the two candidates are equidistant from the centre.

- other people will not enter because the more distant candidate will win

- however, with two candidates at either extreme (beyond 1/6 and 5/6), someone can run in the centre.

The Location model

- Assume two towns, E and W, which can hold 100 people, and that there are 100 Tall people and 100 Short people.

- We model the people as preferring mixed towns, but failing that, they would prefer their own type.

- The game is to choose a town, given that everybody chooses simultaneously, and that if there is no room, the excess is randomised.

- There is an unstable NE when both towns are perfectly mixed (since nobody has an incentive to deviate), but if even one person deviated then there would be an incentive to deviate.

- Despite the maximum payoff being for perfectly mixed towns, there are two stable NEs correspond to segregation.

- Hence initially random starting conditions can lead to segregation.

Mixed strategies

- In the Location model, another stable NE is if everybody chose between cities randomly.

- This is a mixed strategy, i.e a randomisation over the pure strategies. This is a generalisation of a pure strategy, since a pure strategy can be thought of as a mixed strategy with probability 1 for a given choice.

- For example, in rock-paper-scissors, there is no NE in pure strategies, but a mixed-strategy NE is playing each choice with probability 1/3.

- A mixed strategy is denoted by $p_i$, where $P_i(s_i)$ is the probability that $p_i$ assigns to the pure strategy $s_i$.

- The expected payoff of the mixed strategy is the weighted average of expected payoffs of each pure strategy.

- thus the payoff of the mixed strategy must lie within the payoffs of pure strategies.

- hence, if a mixed strategy is a BR, then each of the pure strategies must all be BRs

- furthermore, all of the pure BRs must have the same expected payoff (else you could drop one out to improve payoff).

- Hence it is quite easy to find mixed strategy NEs: find your opponent’s payoffs in terms of your probabilities, then use the fact that each pure strategy must be a best response.

- the implication of this is that many seemingly intuitive strategies do not have the intended consequences.

- for example, increasing the penalty for tax evasion without changing the auditor’s payoffs does not change the amount of tax evasion (though it does reduce the amount of auditing needed).

- to check a mixed NE, we need only check if we can increase the payoff from pure strategy deviations.

- Mixed strategies can also be interpreted as the proportion of players who would pick different pure strategies in a large population.

Evolutionary stability

- We can think of genes (phenotypes) as strategies, and fitness as payoffs.

- In this context we assume that we have a large population and that successful strategies grow (asexual reproduction so no gene redistribution).

- Strictly dominated strategies are not evolutionarily stable (ES).

- In a two player game, if a strategy is not Nash (i.e both players playing s is not a NE), then s cannot be ES because there is a strictly profitable deviation.

- conversely, if a strategy is ES, then the strategy is NE.

- but it is not true that any Nash strategy is evolutionary stable.

- in the below example, $(b,b)$ is a NE but is not evolutionary stable because you can profitably deviate to $a$.

a b a 1, 1 0, 0 b 0, 0 0, 0 - We conclude that strict Nash strategies are evolutionarily stable.

- Formally, in a symmetric 2 player game, the pure strategy $\hat{s}$ is evolutionarily stable in pure strategies if there exists an $\bar{\epsilon} > 0$ such that $\forall \epsilon < \bar{\epsilon}$, i.e “for small $\epsilon$”:

- In other words, for any possible deviant strategy $s’$, the payoff for $\hat{s}$ against the mixed population (including the deviants) is greater than the payoff for $s’$ against the mixed population (including the deviants).

- An alternative definition is that the pure strategy $\hat{s}$ is ES in pure strategies if:

- $(\hat{s}, \hat{s})$ is a strict NE, i.e $u(\hat{s}, \hat{s}) > u(s’, \hat{s}), \forall s’$

- OR $(\hat{s}, \hat{s})$ is a weak NE and $u(\hat{s}, s’) > u(s’, s’)$.

- the second condition states that for an incumbent to be ES, it must do strictly better against the mutant than the mutant does against itself.

- this definition makes it easier to verify that a strategy is ES (compared to the previous one).

- in fact this definition applies directly to the case of mixed strategies, after replacing all s with p.

- ES strategies may not be Pareto efficient, if there are two strict NEs with different payoffs.

Evolutionary stability in mixed strategies

- In the symmetric game of chicken (i.e aggression vs non-aggression), the payoff matrix is as follows:

| a | b | |

|---|---|---|

| a | 0, 0 | 2, 1 |

| b | 1, 2 | 0, 0 |

- There is no symmetric pure-strategy NE, but there is a symmetric mixed-strategy NE with 2/3 aggression and 1/3 non-aggression.

- Mixed NEs cannot be strict by definition, because you are indifferent to the strategies.

- Stable pure populations are called monomorphic, while stable mixed populations are polymorphic.

- An important game in biology is the Hawk-Dove game – this does not refer to different species, but rather aggressive vs non-aggressive strategies.

- two individuals are competing for some prize $v > 0$

- if they both fight for it, the prize is split but each species incurs some cost $c>0$

- if they are both doves, the prize is split equally

- if one is a hawk and one is a dove, the hawk wins the entire prize.

| H | D | |

|---|---|---|

| H | (v-c)/2, (v-c)/2 | v, 0 |

| D | 0, v | v/2, v/2 |

- $(D,D)$ is not a NE so Dove is not an ESS. But $(H, H)$ is a NE if $(v-c)/2 \geq 0$, where the strictness depends on whether the $\geq$ is an equality.

- if $v =c$ (so weak NE), we must check that $u(H,D) > u(D,D)$, which is indeed true. So Hawk is an ESS if $v \geq c$.

- if $c > v$, neither Hawk nor Dove are ESS, so we must consider symmetric mixed strategies

- the result is that $\hat{p} = \frac{v}{c}$ of the population will be hawks.

- The ESS agrees with the intuition that as v increases or c decreases, there are more Hawks (and the converse for Doves).

- the payoff for being a dove is $(1- \frac v c)(\frac v 2)$. As c increases, the payoffs actually increase because the number of fights goes down

- from this analysis, we can infer the payoff matrix by looking at the proportion of Hawks.

Midterm exam

I sat the midterm closed-book and under timed conditions. In reality I probably would have tried to give a bit more detail – hence the current marking may be a bit generous, because if I got the right numerical answer I assumed that my method was correct and gave myself all the marks.

Sequential games

- A very simple model of lending/borrowing is “cash in a hat”: player 1 puts some money in a hat, then player 2 looks at it and can either match it or take the money. If player 2 matches, each player gets more than they put in.

- This is a sequential game because player 2 could observe player 1’s choice (and player 1 knows this is going to be the case).

- These games can be represented as trees and can then be solved with backward induction - starting at leafs then moving towards the root, picking the maximum payoff at each node.

- These games often feature moral hazard - agents are incentivised to do things that lead to overall lower payoff. Hence incentive design is very important in real life.

- e.g. collateral on loans is not meant to give a better payoff to the lender - it is meant to add a penalty to the borrower so they choose the mutually better response

- hence the collateral makes the borrower better off overall

- Removing choices (as long as other players know you removed choices) can lead to better payoffs because it changes their behaviour, e.g. William the Conqueror burning his ships. The Saxons now knew he would have to fight, so they were incentivised to run.

- The temporal aspect of sequential games is not as important as the informational aspect.

First movers

- In the two-firm identical-goods competition model (e.g. Cournout), there is a first-mover advantage. The first mover can maximise their profits by maximising the quantity supplied.

- This first-mover advantage only exists if the first mover makes a tangible commitment – sunk costs can help demonstrate commitment to opponents.

- Corporate espionage can therefore backfire, because if they discover you have a spy, you essentially become the second mover.

- More generally, having more information (when your opponent knows you have the information) can lead your opponents to choose actions that hurt you.

- But the existence of a first-mover advantage depends entirely on the game (e.g. obviously rock-paper-scissors it is better to move second)

- Zermelo’s theorem states that for a two-player perfect information game with a finite number of nodes that results in either Win, Loss (or Tie), then either:

- player 1 can force a win

- player 1 can force a tie

- player 2 can force a win

- Zermelo’s theorem can be proved by induction on the maximum game length N:

- a game tree of depth 1 must be a W, L, or T, since all the leaf nodes are either W, L, or T

- hence for any node in the tree, we can replace its child nodes by W, L, or T all the way to the root.

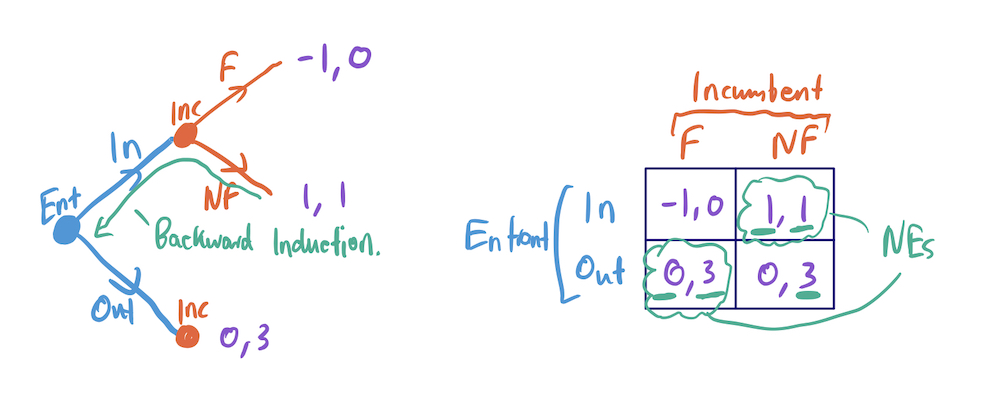

Nash equilibria and backward induction

- In a perfect information game, each player knows the entire move history, i.e at each node, the player knows which node they are at and how the play reached that point.

- a pure strategy for a player in a game of perfect information is a complete plan of action, specifying which action the player will take at each node.

- if we enumerate all possible pure strategies, there will be redundancies corresponding to our responses to moves that the opponent will never make.

- the problem is that this results in NEs that don’t agree with the backward induction result

- E.g the problem of whether or not you should enter a market dominated by an incumbent, where the incumbent would rather not fight:

- backward induction says to enter

- one of the NEs is (In, NF). But there is also a “weird” NE corresponding to (Out, NF).

- the second NE corresponds to believing the non-credible threat that the incumbent will fight you if you enter. It is not credible because you know that if you enter, they won’t fight.

- However, in reality, there may be a sequence of possible new incumbents. Intuition says that it might be a good idea to fight the first few in order to build a reputation that deters future entrants.

- consider 10 sequential possible entrants. The incumbent shouldn’t fight the 10th because there is nobody else for his reputation to apply to.

- by backward induction, the 9th entrant can safely enter because they know that the incumbent won’t fight, since 10 will already enter.

- this leads to the paradoxical conclusion that all possible entrants will enter, so reputation doesn’t matter.

- The resolution to this is that the incumbent can deter entrants by seeming crazy (i.e fighting the first few). The prior probability of $epsilon$ craziness is revised upwards, so later entrants may not want to enter.

- however, this is not a true NE: since the entrants know that even a logical incumbent may wish to act crazy, they shouldn’t update their priors.

- this is known as the chainstore paradox, and is ultimately resolved by factoring in the effort to make decisions, and the levels of reasoning involved.

Duel

- Duel is a sequential game where players take turns to decide whether to shoot each other or to take a step closer, i.e if you shoot and miss you die, but if you wait too late you also die. Some product launches are like this.

- Unlike other games because the strategic decision is when to take an action rather than what action to take.

- We assume that each player’s ability is quantified by their probability of hitting if they shoot at distance d, $p_i(d)$ and that each player’s ability is known by both players.

- This game is not trivial to solve: perhaps the weaker player will shoot first because they know they will lose at closer distances, but then the stronger player may preempt this, etc etc.

- The solution relies on dominance and backward induction:

- if you know that the opponent won’t shoot tomorrow (i.e at $d-1$), you shouldn’t shoot today because you have a chance to get closer.

- if you know that your opponent will shoot tomorrow, you should shoot if your probability of hitting today is better than your opponent’s probability of missing tomorrow, i.e $p_i(d) + p_j(d-1) \geq 1$

- thus there is some $d^*$ at which the first shot should occur – dominance arguments prevent the shot from being taken at any earlier point.

- However, at $d^*$, we need to know what our opponent is going to do. This can be reasoned out with backward induction. The result is that whoever first gets to $d^*$ should shoot.

- A rough rule of thumb is to shoot when the sum of the hit-probabilities is 1.

- Even if you are playing an irrational opponent, you shouldn’t shoot before $d^*$ because it is a dominated strategy. Patience is a virtue!

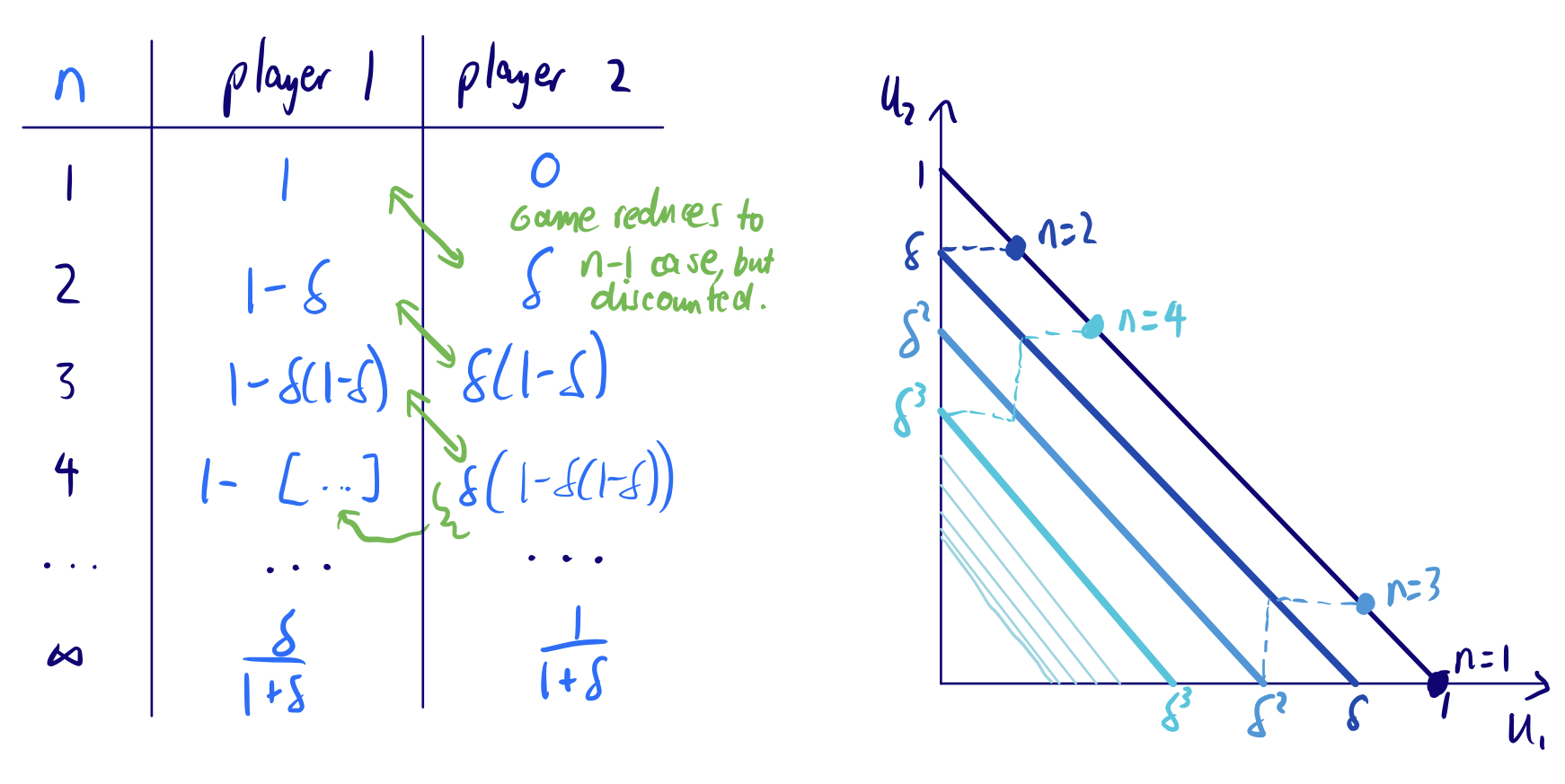

Ultimatums and bargaining

- In the Ultimatum game game, player 1 makes a “take it or leave it offer” to player 2 regarding how \$1 should be split. If player 2 rejects it, neither receives anything.

- By naive backward induction, the receiver should accept any payoff greater than zero (including zero in the limit).

- In the 2-period bargaining game, player 1 makes an offer for how to split \$1, but if player 2 rejects, player 2 now makes an offer to player 1 for how to split $\delta <1$ dollars, which player 1 can accept or reject.

- $\delta$ can be thought of as the discounted present value of \$1 tomorrow (we currently assume it’s the same for both players)

- now player 1 needs to anticipate what player 2 would offer, if they reject the first offer.

- in the 2-stage game, if player 2 rejects, they will offer player 1 zero and keep $\delta$

- so player 1 should initially offer player 2 $\delta$, and keep $1- \delta$.

- In n-period bargaining, player 1 has the advantage if n is odd, otherwise if n is even they have to offer more to player 2, because player 2 makes the final decision.

- using backward induction, the optimum payoff is a geometric series

- however, if offers are made rapidly, $\delta \approx 1$ so the optimal offer in the limit is $(\frac 1 2, \frac 1 2)$

- in reality, one player may be more impatient (i.e higher $\delta$), resulting in a lower absolute payoff.

- This model requires that the value of the item and the time values are all known – that’s why no haggling is involved.

- in bilateral bargaining, people with less wealth may have higher discount rates (need the money more urgently), so do worse.

- if the valuation is unknown, it may not be possible to transact even if the ask is greater than the bid.

Imperfect information

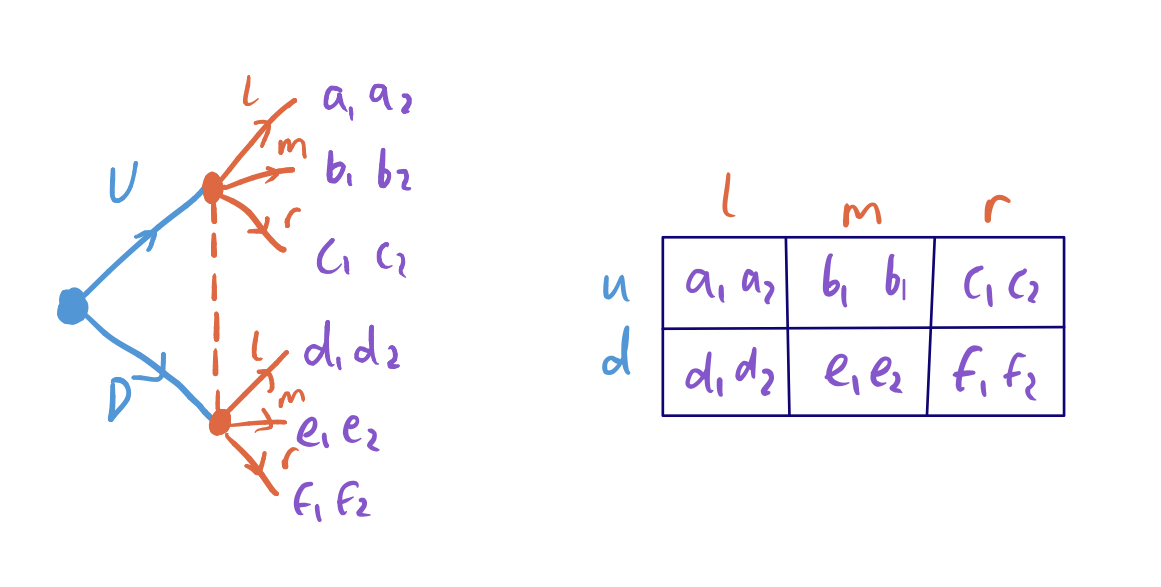

- Some games have both sequential moves and simultaneous moves. These are closely related to games of imperfect information – a simultaneous move can be modelled as player A making a move, then B making a move but not knowing what A played.

- An information set of player i is a collection of player i’s nodes which i cannot distinguish.

- a perfect information game is thus one where all information sets in the game theory only contain one node

- an imperfect information game is the complement of this

- we assume that individual players have perfect recall of their own moves

- In imperfect information games, you can’t just use backward induction because that requires players to know how the history of play arrived at the node.

- A pure strategy for a player in a game of imperfect information is a complete plan of action, specifying which action the player will take for each information set (rather than at each node, as for perfect information games).

- Imperfect information games can be rewritten as payoff matrices – what matters is the transfer of information, rather than the temporal aspect:

- We have seen previously that NEs may not make sense in the context of backward induction. This can be formalised by examining the subgames.

- A subgame is the game corresponding to a subset of a game tree that is also a “proper” game tree. Satisfies the following criteria:

- starts from a single node

- comprises all successors to the node

- it does not break up any information sets

- A Nash Equilibrium is a subgame perfect equilibrium (SPE) if it induces a NE in every subgame of the game.

- the “unrealistic” NEs are those NEs that are not SPEs, because they result in strategies that aren’t NEs for subgames later on.

- SPEs respect both backward induction in the game tree and analysis of the equivalent payoff matrix.

Strategic investments

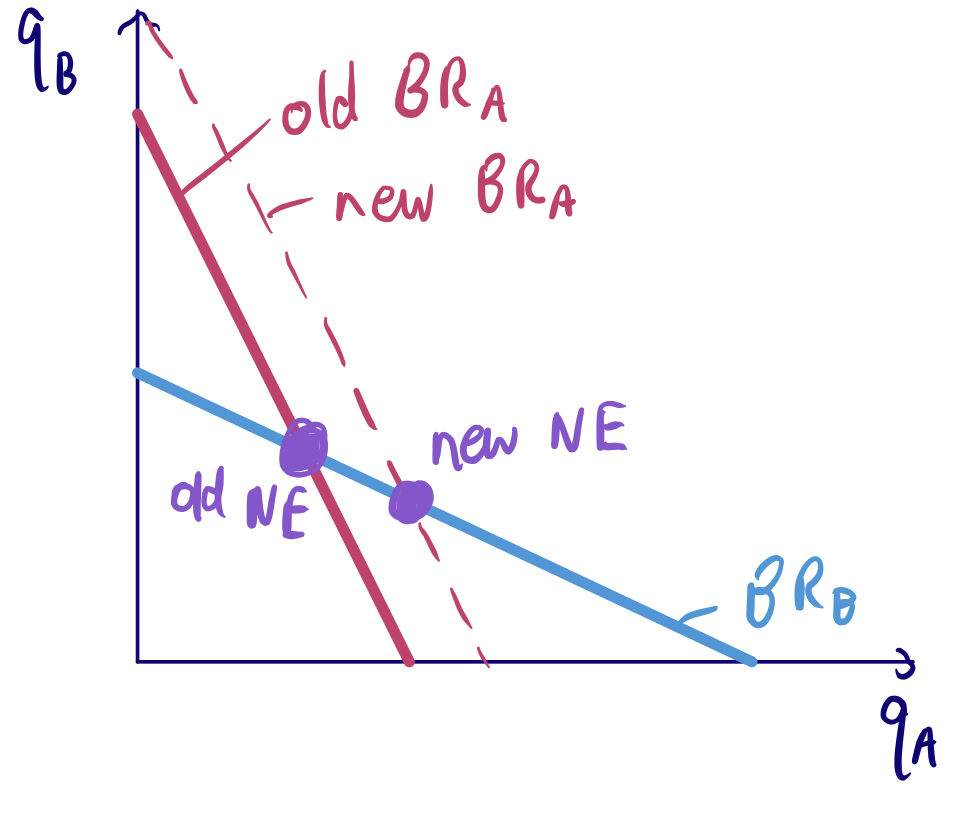

- Consider two firms in Cournot competition, with demand curve $P = 2 - \frac 1 3 (q_A + q_B)$ with quantities in millions and a cost $c = $1$ per tonne.

- the Cournot quantitiy is $q^* = \frac{a-c}{3b}$, i.e 1m units from each firm

- the price is \$1.33/tonne

- The game is to choose whether you as firm A should invest in a machine that costs \$0.7m, but lowers your costs to \$0.5/tonne for the next year.

- The “economics answer” determines the quantity supplied as the intersection between the residual marginal revenue and residual marginal cost (residual meaning after your competitor). Because it is cheaper for you to produce, you produce more, in addition to having a higher margin. This results in a value of \$0.69m, so you shouldn’t invest.

- However, this misses the strategic effect because the Cournot duopoly is a game of strategic substitutes. Since it is cheaper, you produce more. Since you produce more, your opponent’s BR is to produce less (which is good for you!)

- This is in fact a subgame of the original game (invest or not invest) – finding the NE for the subgame shows that including the strategic effect results in a value of \$1m. Hence the SPE is to invest.

Wars of attrition

- In a war of attrition, in each period, each of the two players can choose whether to Fight or Quit. The game ends as soon as someone quits.

- if the other player quits first, you win a prize of value $v$

- for each period in which both players fight, each player pays a cost $c$ (i.e payoff $-c$).

- if both players quit in the same period, they receive 0.

- This is an important game in real life, whether in real wars (WWI trenches), winner-take-all markets, or bribe contests (all-pay auctions).

-

The game is interesting because even rational actors (who ignore sunk costs) can end up losing far more than the potential prize.

- We can start by examining a 2-period game, with no prize if the game doesn’t terminate (assume $v > c$). The second period is a subgame, for which we should separately find the pure NEs and mixed NEs.

- the payoffs for these subgame NEs are continuation payoffs, and we can then use backward induction to analyse the “parent” game.

- the pure NEs are simple: quitters should quit, fighters should fight

- in a mixed NE, each player fights with probability $p^* = \frac{v}{v+c}$, with payoffs $(0, 0)$.

- The parent mixed NE is the same as the subgame mixed NE. Hence it is easy to extend this to an infinite-period game. mixed SPE for the n-period game is to fight with probability $p^*$ at every period.

- Hence even perfectly rational players can play an infinitely long game (though with exponentially decreasing probability).

Repeated games

- Repeated interactions can change the nature of games. The promise of future rewards and the threat of future punishments may provide incentives for good behaviour today.

- Consider the repeated prisoner’s dilemma with a finite number of games:

- in the last round, the dominant strategy is to defect

- by backward induction, at every stage you should defect

- hence repetition does not always improve outcomes

- e.g. the lame duck effect in politics, where politicians find it hard to get things done at the end of their term

- However, there are finite games in which repetition improves payoffs:

| A | B | C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 4, 4 | 0, 5 | 0, 0 |

| B | 5, 0 | 1, 1 | 0, 0 |

| C | 0, 0 | 0, 0 | 3, 3 |

- In this game, the best outcome is $(A, A)$. However, the pure NEs are $(B,B), (C,C)$

- Consider a 2-period version of the game:

- $(A,A)$ will not be played in period 2, since it is not a NE.

- but the strategy “play A in period 1, then play C if opponent played A, B otherwise” is a SPE

- this strategy works because it makes the value of the reward (less punishments) tomorrow greater than the temptation to defect today.

- Hence in multi-period games with more than one NE (with different payoffs), we can use the prospect of playing different NEs tomorrow to provide incentives today – e.g. play one NE as a punishment and another as a reward.

- However, renegotiation can undermine the equilibrium. For example, in the second period of the above game, even if one of the players cheats in the first period, it is mutually beneficial to choose C in the second period (rather than B as the SPE prescribes).

- may be valid if the game is truly finite-period

- but if the other player knows you are open to renegotiation, their incentives change

- real-life example is financial bailouts. Although it is better to bailout once there is a bankruptcy, doing so as a policy creates moral hazard.

- there is a tradeoff between ex ante efficiency and ex post efficiency.

Repeated prisoner’s dilemma

- Intuitively, something is an SPE if:

- One strategy for the infinite prisoner’s dilemma is the Grim Trigger Strategy – cooperate until one player defects, then defect forevermore.

- the temptation to defect today is $3 - 2 = 1$

- the value of the reward tomorrow can be found as the present value of future cooperation payoffs, i.e $\frac{2\delta}{1-\delta}$

- in games, the discount rate can have the same interpretation as in finance, but more commonly it reflects that the game tomorrow may not happen

- if the value of the reward tomorrow is greater than the temptation today, the Grim Trigger Strategy is a SPE.

- this condition is met if $\frac{2\delta}{1-\delta} \geq 1 \implies \delta \geq 1/3$.

- Hence for an ongoing relationship to provide incentives for good behaviour, it helps for there to be a high probability that the relationship continues (i.e high $\delta$, low discount rate).

- The Grim Trigger is very draconian, especially since in real life mistakes happen. Hence may consider a single-period punishment, i.e Tit for Tat.

- both play C by default, then C if both played the same thing yesterday, or D if played differently yesterday.

- does not get stuck in infinite punishment cycle because if you defect today, both of you defect tomorrow, then you play C forevermore.

- this is an SPE iff $\delta \geq 1/2$. Hence although this has lower punishments than the Grim Trigger strategy, you need a smaller discount rate.

- In general, incentives design contains many tradeoffs like this. If you are very impatient, or think a relationship is going to terminate (low $\delta$), you may choose to cheat.

Asymmetric information

- Consider Cournout (quantity) competition with asymmetric information. Firm B does not know Firm A’s cost, while Firm A knows both costs. Assume that Firm A can costlessly and verifiably reveal its costs to B.

- if your costs are lower, you would want to reveal because B would produce less (good for you)

- but you should also reveal middle cost items because otherwise B will assume you have high costs

- hence there is information unravelling because you can’t hide high costs. Silence speaks volumes.

- When it comes to careers, people are trying to convince interviewers that they will be good employees. You may turn to signalling (e.g. education or certification) – it has to be something that is much more costly for bad workers. In this case the “cost” is not financial (since that is the same for good and bad workers), but rather the difficulty of the work.

- this is Spence’s job-market signalling model

- pessimistic model of education because it only considers the “pain” rather than the value of learning

- education increases inequality

Auctions

- Goods for auction can be put on a spectrum of common values (value of good is same for all participants) to private values (single agent’s value is irrelevant to other people).

- In common value auctions, for example a jar of coins, the payoff is $v - b_i$ if your bid $b_i$ is the highest, 0 otherwise.

- each person’s estimate of the true value is $y_i = v + \epsilon_i$.

- if people bid roughly in line with their estimate, the winner will be the person with the highest estimation error.

- this is the winner’s curse.

- in fact, the relevant estimate when bidding is the value of the item given that your guess is higher than everyone else’s bid

- hence you should bid as if you know you win.

- Types of auctions:

- first-price sealed bid (the above)

- Vickery auction – highest bidder pays the second-highest bid.

- Ascending open auction – i.e Ebay

- Dutch auctions – price starts high and comes down until someone buys.

- Dutch auctions are actually equivalent to first-price sealed bids – the highest bidder will win, and the winner doesn’t get to see others’ bids.

- Vickery auctions and ascending open auctions are similar, for example an Ebay auction stops when the second-highest bidder drops out. The difference is that in an open auction, you can get information from others’ bids.

- In a second-price auction, bidding your value is a (weakly) dominant strategy.

- However, in a first-price auction, bidding your value is weakly dominated by shaving down your bid.

- For any kind of private auction in which equilibrium results in the person with the highest value winning the good, the expected revenue is identical. This is the revenue equivalence theorem.