Creating a stock price database with MariaDB and python

One of my interests is exploring the applications of machine learning to financial markets. As part of this hobby, I’ve spent many more hours parsing and processing data than I have actually applying machine learning. I’ve worked broadly with two datasets in particular: historical financial statistics (e.g. P/E ratio, price/book) make up the features that my algorithms learn from, but the actual backbone of any strategy is historical price data.

My main data source has been Yahoo Finance. Although they’ve deprecated their official API, they still have the same data on their website, meaning that it can be scraped if you can be bothered. I discovered a crude but functional way of doing this (detailed in this post), but then discovered an extremely convenient python library that does the same thing much more efficiently, with a direct pandas-datareader interface.

However, it remained a concern for me that one day the winds would change and Yahoo Finance would deprecate this hidden API permanently. So I decided to make a hoard of this data, in the form of a stock price database. I think creating your own securities database is an important step for anyone looking to get into algorithmic investing more seriously, so I’ve decided to share how I’ve done so. As this is my first financial database, there may be inefficiencies in the schema, but overall I believe that the solution presented here is relatively robust, and definitely sufficient for my purposes.

Edit as of Feb 2022: I probably wouldn’t recommend following the steps in this post – there are better resources elsewhere. Nevertheless, I’m leaving this post up for personal nostalgia.

Contents

- Choosing a database management system

- Prerequisites

- Database schema

- Populating the database

- Conclusion

Choosing a database management system

When it comes to choosing a database system, there are a somewhat distressing number of decisions that you have to make. Do you want a relational database or NoSQL? If you choose relational, which system are you going to go with? Within that system, what storage engine should you use?

I think this chart from nuodb sums up the various options quite well:

It was quite clear to me that a SQL relational database was what I wanted, after all, price data is highly structured and I need very quick read speed. But even after narrowing it down to a traditional RDBMS, you still have to choose the exact system. A quick look cut my options down to SQLite, MySQL, or PostgreSQL.

I decided to go with MySQL, because I felt that I didn’t need the application-embedding that SQLite offered, nor did I need all the advanced features of PostgreSQL. In the end though, I chose MariaDB, which is an open-source fork of MySQL that seemed to offer all of the features that MySQL did, with a few minor improvements (see an interesting discussion here). Lastly, you have to choose a storage engine. The default for anything after MariaDB 10.2 is InnoDB, and I felt that the burden of proof was on the alternatives to demonstrate superiority for my purposes. They didn’t do so, hence I stuck with InnoDB. The official documentation gives a very clear exposition on the topic of storage engines.

Prerequisites

A complete guide to setting up MariaDB/MySQL is outside of the scope of this post. Please refer to the official webpages for more. However, if you’re on a mac and already have homebrew, it’s really quite easy:

brew install mariadb

Then it should be a simple matter of starting the MariaDB server and logging in:

mysql.server start

mysql -u root

MySQL and MariaDB are pretty much interchangeable (at least for now), which is why you will interact with MariaDB via mysql commands.

The requirements for this project, which can be installed easily via pip, are as follows:

pandas==0.22.0

PyMySQL==0.8.0

pandas_datareader==0.5.0

fix_yahoo_finance==0.0.21

Lastly, although it’s completely up to you, I would recommend having some other GUI database software on your computer to help visualise things. I like Sequel Pro (macOS only), which is open-source, elegant, and designed specifically for MySQL/MariaDB.

Database schema

A database schema sets out how all of the information is going to be organised in your database. Optimal schema design is a really huge topic that is often the subject of university courses, as well as being a typical interview task for prospective database administrators. I wasn’t naive enough to think that I could come up with the perfect schema from nothing, so I took to google to learn from other people’s mistakes. This was especially important because I knew I would end up with quite a lot of data: I was imagining at least 15 years of daily data for 5000 tickers, which is about 30 million rows. There are lots of conflicting opinions on financial database schema, but in the end I decided to follow the advice of an article from Quantstart. The main advantage of their proposed schema over some of the other suggestions I saw online is flexibility: it really makes no assumptions about what securities you’re interested in. As long as they can be represented as a time series of prices, they’ll fit into the database nicely.

Before getting started generating the tables, we mustn’t forget to generate the database! After logging in to MariaDB, just run the following in the console:

CREATE DATABASE stock_prices;

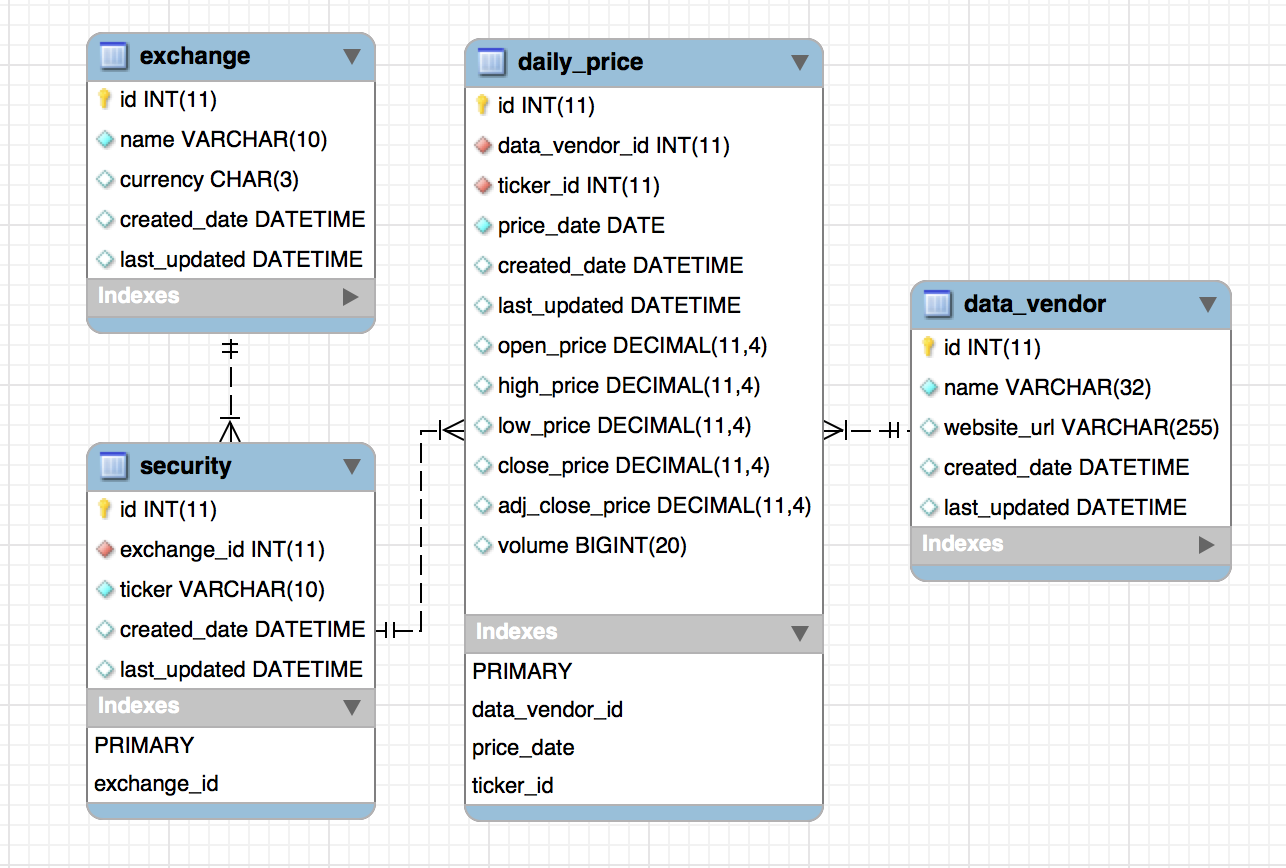

We can then proceed to generate the tables. As per the linked article, we will have four tables: exchange, security, data_vendor, and daily_price.

Just a quick note: if you’re worried about the eventual size of the database, you could consider setting up on an external drive. On unix systems, there is a simple ‘hack’ for this: navigate to your MySQL folder (for me this was /usr/local/var/mysql), find the correct database folder, then drag it to your external drive. Now, create a symbolic link in the mysql directory, by running in terminal:

ln -s [path to drive] [database folder path]

However, I think in most cases this is unnecessary: my 23 million datapoints only take up 3.65 GB.

Table: exchange

The exchange table contains information (the name and currency-traded) of the exchange. This is a parent of table security.

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS `exchange` (

`id` INT(11) NOT NULL AUTO_INCREMENT,

`name` VARCHAR(10) NOT NULL,

`currency` CHAR(3) NULL DEFAULT NULL,

`created_date` DATETIME NULL DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP(),

`last_updated` DATETIME NULL DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP() ON UPDATE CURRENT_TIMESTAMP(),

PRIMARY KEY (`id`))

ENGINE = InnoDB

DEFAULT CHARACTER SET = utf8;

Table: security

security holds all of the relevant information about the actual companies for which we will collect data. Actually the only thing we really need here is the ticker (and which exchange it is traded on), but I thought it might be nice to have some other data like the sector and industry.

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS `security` ;

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS `security` (

`id` INT(11) NOT NULL AUTO_INCREMENT,

`exchange_id` INT(11) NOT NULL,

`ticker` VARCHAR(10) NOT NULL,

`name` VARCHAR(100) NULL,

`sector` VARCHAR(100) NULL,

`industry` VARCHAR(100) NULL,

`created_date` DATETIME NULL DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP(),

`last_updated` DATETIME NULL DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP() ON UPDATE CURRENT_TIMESTAMP(),

PRIMARY KEY (`id`),

INDEX `exchange_id` (`exchange_id` ASC),

INDEX `ticker` (`ticker` ASC),

CONSTRAINT `fk_exchange_id`

FOREIGN KEY (`exchange_id`)

REFERENCES `exchange` (`id`)

ON DELETE NO ACTION

ON UPDATE NO ACTION)

ENGINE = InnoDB

DEFAULT CHARACTER SET = utf8;

The main features of interest are the foreign key on the exchange_id, and the fact that we have added an index on ticker.

Table: data_vendor

Because I was planning to get all of my data from Yahoo Finance, I didn’t think I would need a table like this. However, I suppose that as I cast my net wider in future, it may be useful to have this flexibility.

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS `data_vendor` ;

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS `data_vendor` (

`id` INT(11) NOT NULL AUTO_INCREMENT,

`name` VARCHAR(32) NOT NULL,

`website_url` VARCHAR(255) NULL DEFAULT NULL,

`created_date` DATETIME NULL DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP(),

`last_updated` DATETIME NULL DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP() ON UPDATE CURRENT_TIMESTAMP(),

PRIMARY KEY (`id`))

ENGINE = InnoDB

AUTO_INCREMENT = 3

DEFAULT CHARACTER SET = utf8;

Table: daily_price

This is the real heart of the database. In fact, we could probably denormalise and squish the other tables into this one, but in accordance with the Zen of Python:

Explicit is better than implicit. Sparse is better than dense.

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS `daily_price` ;

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS `daily_price` (

`id` INT(11) NOT NULL AUTO_INCREMENT,

`data_vendor_id` INT(11) NOT NULL,

`ticker_id` INT(11) NOT NULL,

`price_date` DATE NOT NULL,

`created_date` DATETIME NULL DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP(),

`last_updated` DATETIME NULL DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP() ON UPDATE CURRENT_TIMESTAMP(),

`open_price` DECIMAL(11,6) NULL DEFAULT NULL,

`high_price` DECIMAL(11,6) NULL DEFAULT NULL,

`low_price` DECIMAL(11,6) NULL DEFAULT NULL,

`close_price` DECIMAL(11,6) NULL DEFAULT NULL,

`adj_close_price` DECIMAL(11,6) NULL DEFAULT NULL,

`volume` BIGINT(20) NULL DEFAULT NULL,

PRIMARY KEY (`id`),

INDEX `price_date` (`price_date` ASC),

INDEX `ticker_id` (`ticker_id` ASC),

CONSTRAINT `fk_ticker_id`

FOREIGN KEY (`ticker_id`)

REFERENCES `security` (`id`)

ON DELETE NO ACTION

ON UPDATE NO ACTION,

CONSTRAINT `fk_data_vendor_id`

FOREIGN KEY (`data_vendor_id`)

REFERENCES `data_vendor` (`id`)

ON DELETE NO ACTION

ON UPDATE NO ACTION)

ENGINE = InnoDB

DEFAULT CHARACTER SET = utf8;

Notice the indexes (I believe ‘indices’ is incorrect in this context) on price_date and ticker_id: these are important, because for the most part I know I will be wanting to select stock prices either by date or by ticker.

Putting it all together, we have the following ER diagram:

Populating the database

Let’s start by connecting to the database via python. We could do this via an ORM, but it might be a bit simpler to use a MySQL interface. As seems to be a recurring theme, there are many options for interacting with MariaDB from python. In previous projects I had used MySQLdb, which is generally straightforward but a hassle to install. In order to make this tutorial simpler, I’ve chosen to use a popular pure-python alternative, PyMySQL – functionality is almost identical, but it is much easier to install. Let’s proceed. The top of our python file will begin with the relevant imports.

import time

import pandas as pd

from pandas_datareader import data as pdr

import pymysql.cursors

import fix_yahoo_finance as yf

yf.pdr_override()

Connecting to the database is very simple; if you are having a problem here, it is likely because of the MySQL login details.

conn = pymysql.connect(host='localhost',

user='root',

db='stock_prices')

cursor = conn.cursor()

Just a quick note: it is quite difficult to format the code properly for these blog posts, so if you are copy-pasting (which I don’t recommend!) then please be aware that there are some forced line breaks below that will raise errors in python (particularly within long SQL statements).

Adding an exchange and a list of securities

We will start by manually writing an exchange to the database:

sql = "INSERT INTO exchange (name, currency) VALUES ('NYSE', 'USD')"

cursor.execute(sql)

conn.commit()

As a rule of thumb, after every set of like database operations (e.g. after you’ve added/deleted a few things), you should throw in a conn.commit() which makes the changes permanent.

After adding the exchange, we need to give it some children (i.e securities). Luckily, there are official lists in csv format containing all of the tickers in the NYSE, NASDAQ and AMEX. Head to that link and download the NYSE list. Within my project directory, I put this in a subfolder called data, and named it nyse_tickers.csv. Parsing these tickers is not very difficult:

nyse = pd.read_csv('data/nyse_tickers.csv')

print("Number of NYSE tickers:", len(nyse))

nyse.drop(['LastSale', 'MarketCap', 'IPOyear', 'Summary Quote',

'Unnamed: 9', 'ADR TSO'], axis=1, inplace=True)

nyse.columns = ['ticker', 'name', 'sector', 'industry']

nyse['exchange_id'] = 1

nyse = nyse[cols[-1:] + cols[:-1]]

Notice that I’ve done some weird manipulations with the column names, and I’ve added a new constant column corresponding to the exchange ID of NYSE (in our exchange table). This allows for an elegant snippet to add the data to our database:

for row in nyse.itertuples(index=False):

try:

cursor.execute("INSERT INTO security (exchange_id,

ticker, name, sector, industry) VALUES (%s, %s, %s, %s, %s)",

row)

except:

# Assume that the exception is because sector

# and/or industry are missing

cursor.execute("INSERT INTO security (exchange_id,

ticker, name) VALUES (%s, %s, %s)", row[:3])

conn.commit()

Adding price data

Before we add price data, we must manually add a data vendor:

sql = "INSERT INTO data_vendor (name, website_url) VALUES " + \

"('YahooFinance', 'https://finance.yahoo.com')"

cursor.execute(sql)

conn.commit()

YAHOO_VENDOR_ID = 1

Next, we list the securities that have been added, so that we know the tickers for which we should download data.

all_tickers = pd.read_sql("SELECT ticker, id FROM security", conn)

ticker_index = dict(all_tickers.to_dict('split')['data'])

tickers = list(ticker_index.keys())

In principle, now all we have to do is iterate over the list of tickers, download data from pandas-datareader, then write to daily_price. This can be implemented very simply as follows:

for ticker in tickers:

# Download data

df = pdr.get_data_yahoo(ticker, start=start_date)

# Write to daily_price

for row in df.itertuples():

values = [YAHOO_VENDOR_ID, ticker_index[ticker]] + list(row)

cursor.execute("INSERT INTO daily_price (data_vendor_id,

ticker_id, price_date, open_price, high_price, low_price,

close_price, adj_close_price, volume) VALUES

(%s, %s, %s, %s, %s, %s, %s, %s, %s)",

tuple(values))

In practice, however, we need to add some fault tolerance. For example, I have found that pandas-datareader inconsistently throttles. One solution is to split the download into chunks, and keep track of failed downloads. Throwing a couple of try/except statements in there too, we get the following two methods:

def download_data_chunk(start_idx, end_idx, tickerlist,

start_date=None):

"""

Download stock data using pandas-datareader

:param start_idx: start index

:param end_idx: end index

:param tickerlist: which tickers are meant to be downloaded

:param start_date: the starting date for each ticker

:return: writes data to mysql database

"""

ms_tickers = []

for ticker in tickerlist[start_idx:end_idx]:

df = pdr.get_data_yahoo(ticker, start=start_date)

if df.empty:

print(f"df is empty for {ticker}")

ms_tickers.append(ticker)

time.sleep(3)

continue

for row in df.itertuples():

values = [YAHOO_VENDOR_ID, ticker_index[ticker]] + \

list(row)

try:

sql = "INSERT INTO daily_price (data_vendor_id,

ticker_id, price_date, open_price,

high_price, low_price, close_price,

adj_close_price, volume)

VALUES (%s, %s, %s, %s, %s, %s, %s, %s, %s)"

cursor.execute(sql, tuple(values))

except Exception as e:

print(str(e))

conn.commit()

return ms_tickers

def download_all_data(tickerlist, chunk_size=100,

start_date=None):

# Hacky snippet to get the ceiling

n_chunks = -(-len(tickerlist) // chunk_size)

ms_tickers = []

for i in range(0, n_chunks, chunk_size):

# This will download data from the earliest possible date

ms_from_chunk = download_data_chunk(i, i+chunk_size,

tickerlist,

start_date)

ms_tickers.append(ms_from_chunk)

# Check for possible throttling

if len(ms_from_chunk) > 40:

time.sleep(120)

else:

time.sleep(10)

return ms_tickers

After this, you can do a second pass over the missing tickers to try to get as much data as possible.

Updating data

At specified intervals (perhaps via a cron job), you may want to update the prices in the database. Here’s a quick script to do that:

def update_prices():

# Get present tickers

present_ticker_ids = pd.read_sql("SELECT DISTINCT ticker_id

FROM daily_price",

conn)

index_ticker = {v: k for k, v in ticker_index.items()}

present_tickers = [index_ticker[i]

for i in list(present_ticker_ids['ticker_id'])]

# Get last date

sql = "SELECT price_date FROM daily_price WHERE ticker_id=1"

dates = pd.read_sql(sql, conn)

last_date = dates.iloc[-1, 0]

download_all_data(present_tickers, start_date=last_date)

Conclusion

I hope this post has given you an idea of how you might go about creating your own securities database. In future, I’m quite keen to add to this database new tables for stock fundamental data as well, but this would be much more complicated unless I’m only interested in a specific list of features. Otherwise, NoSQL might be a better option.

But for now, I’m happy with the price database. Looking back, I think it was a very worthwhile time investment – I have already made quite significant use of the database and am enjoying the convenience. I can now prototype algorithms much faster, without the hassle of having to re-download data every time or find the csv files somewhere on my filesystem. Not to mention the fact that I won’t be as heavily affected by the whims of some Yahoo Finance team-leader who decides to change the UI again.