An asymmetric bet on interest rates

In a classic scene of No Country For Old Men, Javier Bardem’s character ominously asks a shopkeeper: “what’s the most you ever lost on a coin toss?”. The shopkeeper says that he doesn’t know – this is probably quite a reasonable response given that for a fair coin, one has little reason to make a bet since your expected value (EV) is zero. Yet retail investors seem to make coin-toss bets all the time: they conclude that based on their analysis, a certain stock is a buy (i.e it has positive expected value). But they often forget to account for model risk – the risk that their analysis itself is faulty.

There is plenty of research to show that in actual fact, the buy/sell decisions of (retail) investors may as well be coin flips. Steve Cohen, the legendary hedge-fund manager, points out that his best portfolio managers get the direction of stock movement right only 56% of the time. However, the key to their success is the asymmetric payoff. When they are right, they ride the stock up to significant gains, but when they are wrong they are quick to cut losses. Let’s assume that whenever they are right, the stock goes up 30%, but if the stock is going down they will cut their losses at 5%. The EV is then calculated as follows:

\[\text{EV} = 0.56 \times 30\% + (1-0.56) \times (-5\%) \approx 17\%\]Hence despite the “low accuracy”, the expected return on a single trade is an admirable 17%. We can use EV calculations to understand the profitability of all kinds of trading setups – some funds choose to make bets that have a less than 5% chance of being right, but will return 100x if they are. Other players, particularly market makers and option sellers, choose to make fractions of cents on every trade, but often have significant tail risk. In this post, I want to present an idea I had at the start of summer for an asymmetric bet on US interest rates.

Outline of the pitch

It was July 2019: the height of the trade war, Brexit uncertainties alive as ever, people wondering if the decade-long bull market was going to come to an end (having forgotten about December 2018) – all eyes were on the Federal Reserve and it seemed that every day financial news sources had a different analysis of what would happen to interest rates. I was reading the Financial Times when a statement popped up that really excited me:

the market is pricing in an 100% probability of a rate cut of 25bps or more

This statement provides an interesting opportunity to make a positive EV bet because of the asymmetry it presents. When the market is so confident that interest rates will be cut, you are getting excellent odds to make a bet on the opposite outcome (i.e rates held constant or increasing), even if you think that’s quite unlikely.

Concretely, my proposal was to make a hawkish bet, i.e betting that interest rates will either stay the same or go up. Because the market thinks that there is an “100% chance” of a cut, if the rates are indeed cut, then I wouldn’t pay much for being wrong. However, on the off chance I’m right, my payoff could be large.

In the rest of the post, we will discuss how to actually bet on interest rates, how the market-implied probability of a rate cut is calculated, and a post-mortem of my pitch.

The Federal Reserve and interest rates

Banks in the US are legally required to keep some cash in the Federal Reserve. Amounts in excess of this minimum reserve can be lent as an unsecured loan to other market participants; the interest rate on these loans is the Federal funds rate.

These loans are negotiated by the borrowers and lenders (who are usually financial institutions). Why, then, do people always talk about the Fed hiking/cutting rates? The answer is that although the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) doesn’t set interest rates, it does set a “target rate”. This is more than just words, because the Fed can conduct open-market actions to help move the overnight rate towards its target – this typically consists of either buying or selling government bonds. For example, when the Fed buys government bonds, there is more money in the system so people will pay less to borrow money (i.e interest rates go down).

Fed funds futures

A forward contract is an agreement between a buyer and a seller to transact in a particular quantity of some item, at a specified date and price in the future. For example, a soybean farmer might want to lock-in a sale price for their soy beans before the harvest and might thus agree to sell 5,000 bushels exactly 6 months from now (May 2020), at a price of 8.85 per bushel. Come May 2020, the farmer delivers the soybeans to the buyer and is paid $\$8.85 \times 5000 = \$44,250$.

A futures contract is essentially the same, except that the contracts are standardised, allowing them to be traded on an exchange. A good way of thinking about this is that there are pieces of paper going round saying “by holding this paper, I agree that on the 1st of May 2020, I will deliver 5000 of bushels of soybeans for the price of $8.85 per bushel” – these pieces of paper can then be bought and sold. Note that you don’t actually have to physically deliver the underlying asset (in most cases) – the usual practice is to settle in cash, for example by paying the deliveree the current market price of the asset.

There is a lot more that could be said about futures, both on the theory side (no-arbitrage pricing) to the practicalities (margin, roll, and covering positions), but the key takeaway is that a futures contract is a way of speculating on the price of some underlying asset. This is a useful way of thinking about it, particularly in the context of underlying assets that are not physical commodities and hence cannot be delivered.

In this vein, a Federal funds futures contract is a piece of paper saying that you will be paid an amount of money that depends on the Federal funds rate at a certain date in future. For example, let’s say that our simple conversion scheme is to take the Federal funds rate as a percentage, multiply it by \$100, and pay out that amount e.g. on the day that the contract expires, if the Fed funds rate is 2.1%, you will be paid \$210. How much would you pay for this piece of paper today? Clearly that depends on what you think is going to happen to interest rates. This is really the heart of a Fed funds futures contract – it’s a piece of paper whose value depends on the Federal funds rate at some date in the future.

There is one minor annoyance, however. For historical reasons, futures brokers prefer standardised scales, so the Fed funds futures trade with the “IMM price”, i.e the price index of the contract is given by:

\[\text{Futures price} = 100 - \text{interest rate}\]Thus a value of 97.5 corresponds to a Fed funds rate of 2.5%. There is some additional nuance that I don’t particularly want to go into (for example, the interest rate used in the above calculation is actually the 30 day rolling mean of Fed funds rates), but any interested readers can have a look at the actual contract specification.

This notwithstanding, the essential point is that Fed funds futures give us a direct way to speculate on US interest rates. In the above example, if we think the Fed is going to cut rates from 2.5% to 2.25%, we would go long a Fed funds future if it were trading below 97.75, because after the rate cut, the contract would settle at 97.75 (more than what we paid for it). Likewise if we have a hawkish view, we would short the Fed funds future.

The market-implied probability of a rate cut

Clearly, if the current interest rates are 2.5% and the Fed funds futures are priced at 98 (corresponding to a 2% rate), we know that the market thinks a rate cut will happen. But how was financial news quantifying the market-implied probability of a rate cut?

As it happens, the CME group runs a wonderful web app called the CME FedWatch Tool, which provides a whole host of analytics regarding FOMC meetings – including the probability of a certain rate movement. Their methodology is detailed on the website, but a brief summary is as follows.

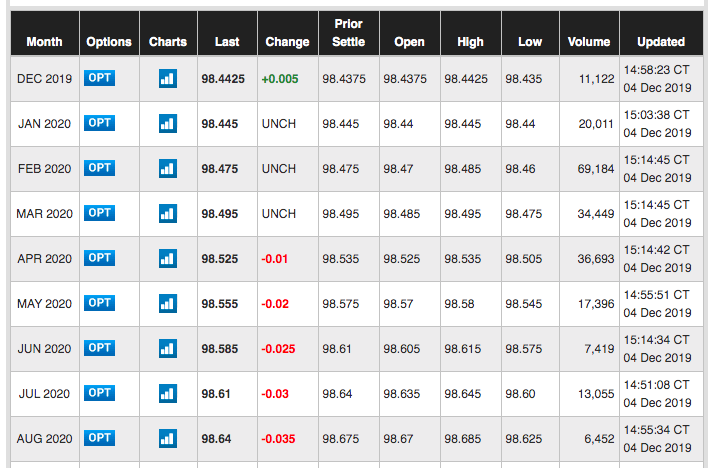

The first thing to note is that Fed Funds futures contracts can be bought with expiries on calendar months up to about 3 years from now. That sentence was terribly worded, but I really can’t think of a better phrasing, so I’m just going to use a picture:

This is incredibly useful because it allows us to isolate the effect of a given month’s FOMC meeting. For example, if there is a meeting on 31 July, we need only consider the contract expiring 1 July and the contract expiring 1 August to understand the market’s view of the meeting. Let’s go through a very simple example of a probability calculation to estimate the probability of a 25bps cut (using made-up data):

Fed funds future (exp 1 Jul) = 97.60

Fed funds future (exp 1 Aug) = 97.70

implied rate (1 Jul) = 100 - 97.60 = 2.40

implied rate (1 Aug) = 100 - 97.70 = 2.30

P(25bps cut) = (2.40 - 2.30) / 0.25 = 40%

P(no cut) = 1 - P(cut) = 60%

The only mysterious step is possibly the P(cut) step, but this can be easily reasoned out. If there is a 25bps rate cut, the Fed-funds-implied rate will go from 2.40 to 2.15 by expiry. But the market has priced this at 2.30 instead. How far “along” is 2.30 between 2.40 and 2.15? Ten twenty-fifths of the distance. This must be the market-implied probability.

Of course, there is added complexity in that the above analysis has only dealt with a very narrow question: what is the probability of a 25bps cut vs no cut. In reality, the Fed can leave rates the same, or cut/raise them by any multiple of 25bps. The full calculation is essentially the same as the above, just with a bit of mathematical trickery to adjust for the different branches.

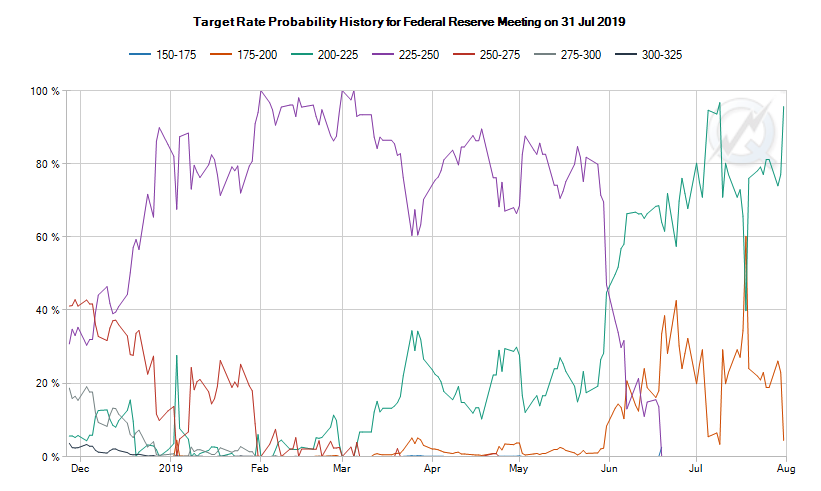

Now that we understand how these probabilities are calculated, we can look at the data. This chart shows all of the market-implied probabilities leading up to the 31/7/2019 FOMC meeting. For context, I was pitching this idea at the start of July 2019 and the Fed’s target rate was 225-250bps:

We can see that by mid-June, the probability that rates would be held at 225-250bps went to zero (the nosedive of the purple line). This means that Fed funds futures were priced such that there was an 100% chance of a rate cut.

My estimate of the probability of a rate cut

Having seen what the market expects, we can now begin to think about some reasons that the market could be wrong. I think there are three plausible reasons:

-

In July 2019, the US economy was chugging along perfectly well. In June, nonfarm payrolls rose 224,000 (well above market expectations); the nonfarm payroll numbers are one of the many key job statistics that people keep an eye on because they give a great look into the health of the US economy.

-

Related to the above, a major component of the Fed’s mandate is to keep inflation at around 2%. When the economy is “heating up” too much (with high inflation), the Fed may want to raise rates to cool things down. Likewise, if the economy is cooling down, the Fed may want to lower the target rate to encourage people to take money out of their bank accounts and spend! Between January and June 2019, US inflation had steadily climbed from around 1.5% to 2.0%, in absence of any open-market action from the Fed. Thus it could be argued that there is no reason for them to cut rates in the July FOMC meeting.

-

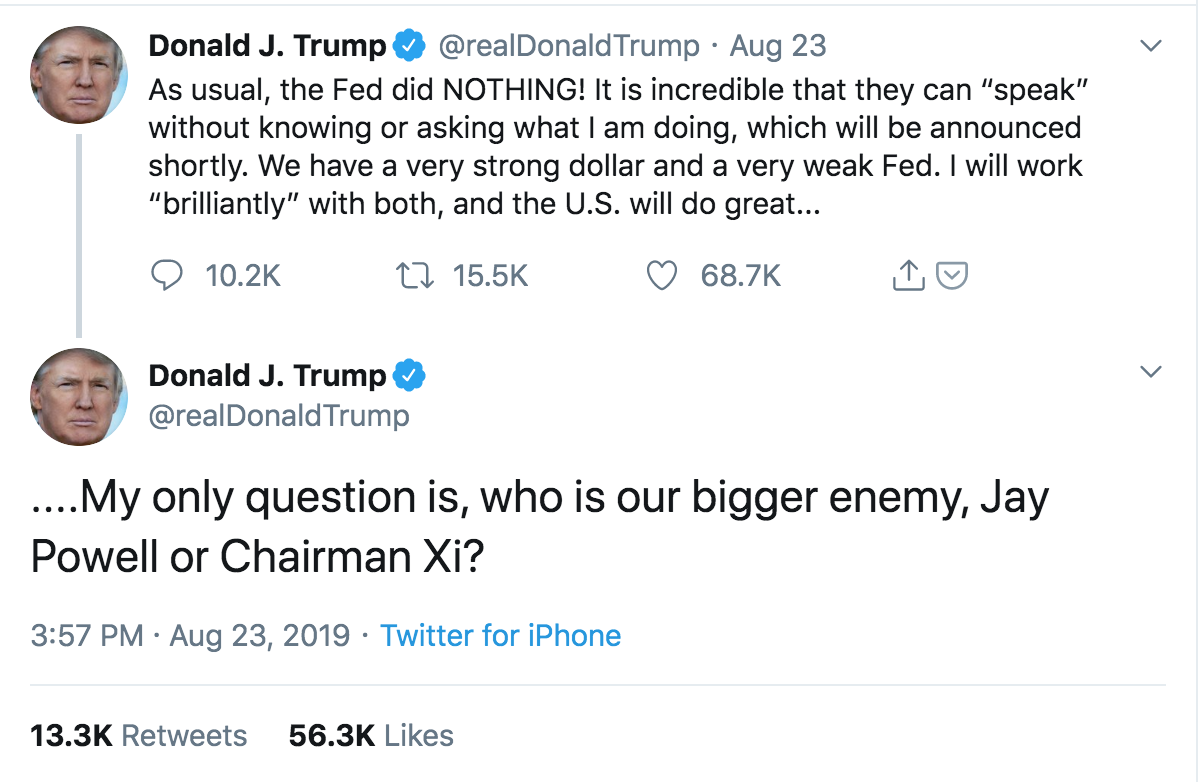

This is a “softer point”, but one thing I have always found interesting is Jerome Powell’s levelheadedness in the face of Donald Trump, who has issued many scathing comments (over Twitter, no less) of the Fed for not being looser with monetary policy. It is quite possible that Powell would want to remain defiant (and assert the Fed’s independence) by not “giving in” to Trump’s demands.

I haven’t gone into too much detail for the above points because it doesn’t really matter. The fundamental argument in the post is that as long as there exists a nonzero probability of a rate-hold (or rate hike), we are able to make a positive EV bet. To elucidate this, let’s say that based on my analysis above I’m willing to say that there’s just a 2% chance of a rate cut.

| Interest rate | Market-implied probability | My estimated probability |

|---|---|---|

| 225-250 (hold) | 0% | 2% |

| 200-225 (25bps cut) | 97% | 96% |

| 175-200 (50bps cut) | 3% | 2% |

Let’s assume that we are dealing with a contract that expires right after the FOMC meeting. Given the market-implied probabilities, we can estimate the price of the future’s contract let’s say the Fed funds futures contract (which expires right after the FOMC meeting) is trading at 97.883 – a number I calculated as below:

\[\text{market price} = 100 - (0.97 \times 212.5 \text{bps} + 0.03 \times 187.5 \text{bps}) = 97.883\]Using my estimated odds (different from the market’s!), the fair price of the Fed funds future (ignoring pedantry regarding the time-value of money) is:

\[\text{fair price} = 100 - (0.02 \times 237.5\text{bps} + 0.96 \times 212.5 \text{bps} + 0.02 \times 187.5 \text{bps}) = 97.875\]Hence my hawkish bet (shorting the futures contract) would result in a profit of about \$33 per contract (according to the contract spec, each contract settles for \$4167 times the price index). You might think that 0.08% profit sounds paltry, but it should be remembered that the beauty of futures is leverage. For this particular contract, you would only have to put up about \$400 of maintenance margin, so the actual percentage profit would be about 8%. This isn’t bad at all, considering the time horizon of this bet is a few weeks.

Conclusion

Unsurprisingly, the Fed decided to cut rates by 25bps, citing weak global growth and trade tensions. However, I don’t think this pitch was incorrect. The point is not that I thought rates would be held steady, but that I was willing to assign this outcome a higher probability than the market was.

I ended up pitching this idea, together with three other students, to a panel of managing directors at J.P. Morgan as part of an industry insight event. They were sceptical initially, but were quite intrigued once I had made it sufficiently clear that this was really a play on market expectations rather than interest rates directly. On a side note, I knew that a successful pitch here could result in a front-office summer internship offer at JPM so perhaps there was another dimension to this asymmetric bet…

If there’s anything you should take away from this post, it is this: I am certainly not claiming to know more than economists about what the Fed is going to do. What I am saying is that whenever the market is so sure that something is going to happen (or never going to happen!), there could be a good opportunity for a highly asymmetric bet.